Appearance

小学生空间认知与数学发展关系

下面是相关的论文英文和中文同译只共参考, 有译的不准确的地方请指正.

Abstract

Spatial thinking is an important predictor of mathematics. However, existing data do not determine whether all spatial sub‐domains are equally important for mathematics outcomes nor whether mathematics–spatial associations vary through development. This study addresses these questions by exploring the developmental relations between mathematics and spatial skills in children aged 6–10 years (N = 155). We extend previous findings by assessing and comparing performance across Uttal et al.'s (2013), four spatial sub‐domains. Overall spatial skills explained 5%–14% of the variation across three mathematics performance measures (standardized mathematics skills, approximate number sense, and number line estimation skills), beyond other known predictors of mathematics including vocabulary and gender. Spatial scaling (extrinsic‐static sub‐domain) was a significant predictor of all mathematics outcomes, across all ages, highlighting its importance for mathematics in middle childhood. Other spatial sub‐domains were differentially associated with mathematics in a task and age‐dependent manner. Mental rotation (intrinsic‐dynamic skills) was a significant predictor of mathematics at 6 and 7 years only which suggests that at approximately 8 years of age, there is a transition period regarding the spatial skills that are important for mathematics. Taken together, the results support the investigation of spatial training, particularly targeting spatial scaling, as a means of improving both spatial and mathematical thinking.

KEYWORDS

development, mathematics, spatial cognition

摘要:

空间思维是数学能力的重要预测因素。然而,现有数据并未确定所有空间子领域对数学结果的影响是否相同,以及数学与空间的关联是否随着发展而变化。本研究通过探索6-10岁儿童(N = 155)的数学和空间技能发展关系来回答这些问题。我们通过评估和比较Uttal等人(2013年)提出的四个空间子领域的表现,扩展了先前的研究结果。整体空间技能在三个数学表现指标(标准化数学技能、近似数感和数线估计技能)的变异中解释了5%至14%的差异,超过了其他已知的数学预测因素,包括词汇和性别。空间缩放(外在静态子领域)是所有年龄段上所有数学结果的显著预测因素,突出了它在中小学阶段数学中的重要性。其他空间子领域以任务和年龄相关的方式与数学相关。心理旋转(内在动态技能)只在6岁和7岁时是数学的显著预测因素,这表明在大约8岁左右存在一个关于对数学重要的空间技能的过渡期。综合而言,研究结果支持进行空间训练的探索,特别是针对空间缩放,作为提高空间和数学思维能力的手段。

关键词:

发展、数学、空间认知

1 INTRODUCTION

Spatial thinking has previously been identified as a significant predictor of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) success in adults (Shea, Lubinski, & Benbow, 2001; Wai, Lubinski, & Benbow, 2009). More recently, behavioural links between spatial and mathematical skills have also been reported in pre‐school and primary school children (e.g. Gilligan, Flouri, & Farran, 2017; Verdine et al., 2014). Despite reported associations between spatial and mathematical skills at both behavioural and neural levels (Cutini, Scarpa, Scatturin, Dell'Acqua, & Zorzi, 2014; Hubbard, Piazza, Pinel, & Dehaene, 2005; Winter, Matlock, Shaki, & Fischer, 2015), not all studies that have attempted transfer of spatial training gains to mathematics are successful (Cheng & Mix, 2014; Hawes, Moss, Caswell, Naqvi, & MacKinnon, 2017; Hawes, Moss, Caswell, & Poliszczuk, 2015; Lowrie, Logan, & Ramful, 2017). This might be attributable to the fact that spatial and mathematical thinking are often treated as unitary constructs. However, it is unlikely that all spatial and mathematical sub‐domains are associated to the same degree. A precursor to effective training must involve more, fine grained evaluation of spatial skills and their relations to particular aspects of mathematics. This would enable effective selection of training targets, increasing the likelihood of developing successful training interventions.

1 简介

空间思维被认为是成年人在科学、技术、工程和数学(STEM)领域取得成功的重要预测因素(Shea、Lubinski和Benbow,2001;Wai、Lubinski和Benbow,2009)。最近的研究还发现学前和小学儿童的空间技能和数学技能之间存在行为上的联系(例如Gilligan、Flouri和Farran,2017;Verdine等,2014)。尽管有研究报告称空间技能和数学技能在行为和神经水平上存在关联(Cutini、Scarpa、Scatturin、Dell'Acqua和Zorzi,2014;Hubbard、Piazza、Pinel和Dehaene,2005;Winter、Matlock、Shaki和Fischer,2015),但并非所有试图将空间训练成果应用于数学方面的研究都取得成功(Cheng和Mix,2014;Hawes、Moss、Caswell、Naqvi和MacKinnon,2017;Hawes、Moss、Caswell和Poliszczuk,2015;Lowrie、Logan和Ramful,2017)。这可能是因为空间思维和数学思维通常被视为单一结构。然而,不同的空间和数学子领域之间的关联程度不同。为了有效的训练,需要对空间技能进行更加详细和精细的评估,并了解其与特定数学方面的关系。这将有助于有效选择训练目标,并提高开发成功的训练干预措施的可能性。

1.1 Defining spatial thinking

As described by Newcombe (2018), “any kind of action in a spatial world is in some sense spatial functioning, and hence can sensibly be called spatial cognition”. Given the wide scope of spatial cognition, it is unsurprising that spatial research has been complicated by variations in both the terminology and typology used in the domain. For example, attempts at defining a typology for spatial thinking have been approached from an array of perspectives including psychometric, cognitive and theoretical approaches (Linn & Petersen, 1985). In this study, spatial thinking is explored in the context of Uttal et al.'s (2013) theoretical classification of spatial skills (also see Newcombe & Shipley, 2015). The selection of this model was based on the extensive neurological, behavioural and linguistic evidence supporting it (Chatterjee, 2008; Hegarty, Montello, Richardson, Ishikawa, & Lovelace, 2006; Palmer, 1978; Talmy, 2000).

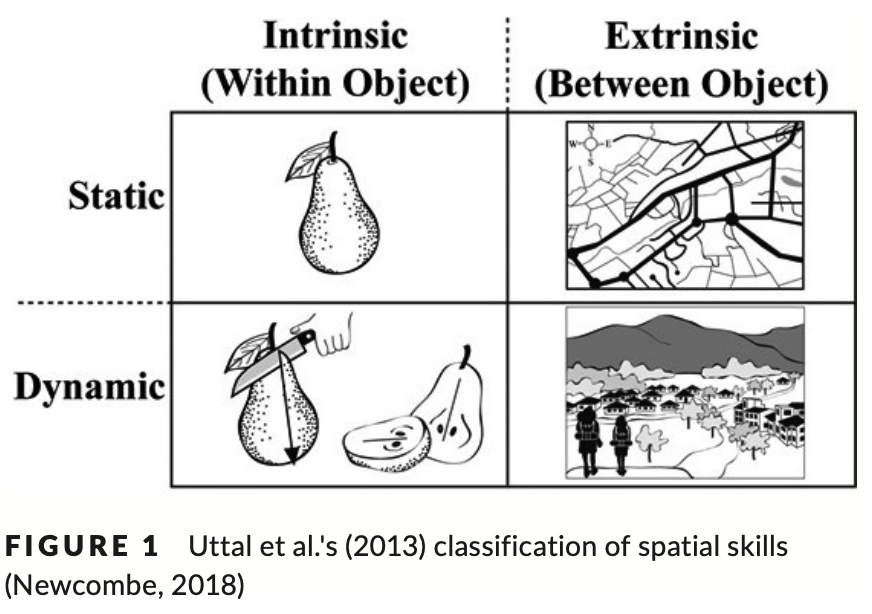

Using two fundamental distinctions between intrinsic and extrinsic, and static and dynamic representations respectively, Uttal et al. (2013) propose a two by two classification of spatial thinking. Intrinsic representations relate to the structure and size of individual objects, their parts and the relationship between these parts. Conversely, extrinsic representations are those pertaining to object locations, the relationship between different objects, and the position of objects relative to their reference frames. Within the second distinction, dynamic representations require transformations or manipulations such as scaling, rotating, folding or bending. For static spatial representations, no movement or transformation is required. In combination, Uttal et al.'s (2013) two by two classification renders four spatial sub‐domains including intrinsic‐static, intrinsic‐dynamic, extrinsic‐static and extrinsic‐dynamic sub‐domains (see Figure 1). In the current study, developmental and individual differences in spatial thinking are measured across each of Uttal et al.'s (2013) spatial categories using a carefully selected task to target each individual sub‐domain.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

• Spatial skills explained 5%–14% of the variation across three mathematics performance measures (standardized mathematics skills, approximate number sense and number line estimation skills).

• Spatial scaling (extrinsic‐static thinking) was a significant predictor of all mathematics outcomes at all ages between 6–10 years.

• Different spatial sub‐domains were differentially associated with mathematics in a task and age dependent manner.

• Spatial training is proposed as a means of improving both spatial and mathematical thinking.

1.1 定义空间思维

正如Newcombe(2018年)所述,“在空间世界中的任何形式的行动在某种程度上都是空间功能,因此可以合理地称之为空间认知”。鉴于空间认知的广泛范围,不难理解空间研究在术语和分类上存在的复杂性。例如,关于空间思维的分类尝试来自于心理测量、认知和理论等多个角度(Linn&Petersen,1985)。在本研究中,空间思维在Uttal等人(2013年)对空间技能进行的理论分类的背景下进行了探讨(另请参见Newcombe&Shipley,2015)。选择这个模型是基于大量支持它的神经、行为和语言证据(Chatterjee,2008;Hegarty,Montello,Richardson,Ishikawa和Lovelace,2006;Palmer,1978;Talmy,2000)。

Uttal等人(2013年)根据内在和外在以及静态和动态表示的两个基本区别,提出了空间思维的二分法分类。内在表示与个体对象的结构、大小、部分及其之间的关系有关。相反,外在表示与对象位置、不同对象之间的关系以及对象相对于参考框架的位置有关。在第二个区别中,动态表示需要缩放、旋转、折叠或弯曲等转换或操作。静态空间表示不需要移动或转换。结合起来,Uttal等人(2013年)的二分法分类形成了四个空间子领域,包括内在-静态、内在-动态、外在-静态和外在-动态子领域(见图1)。在本研究中,使用精心选择的任务来针对每个子领域,测量了空间思维在Uttal等人(2013年)的空间类别中的发展和个体差异。

研究亮点:

• 空间技能解释了三个数学表现指标(标准化数学技能、近似数感和数线估计技能)中5%–14%的差异。

• 空间缩放(外在静态思维)是6-10岁所有年龄段的数学成绩的重要预测因素。

• 不同的空间子领域以任务和年龄相关的方式与数学有不同的关联。

• 研究表明,空间训练可以作为提高空间和数学思维的一种手段。

1.2 Defining mathematical thinking

Like spatial thinking, mathematics is not a unitary construct but requires a multitude of skills and competencies. This study uses Von Aster and Shalev's (2007) model of numerical cognition which posits that individuals are equipped with an innate, core system for representing number, the approximate number system (ANS). The ANS stores approximate representations of numerical magnitude in the brain without symbols (Cordes, Gelman, Gallistel, & Whalen, 2001; Feigenson, Dehaene, & Spelke, 2004). These representations are proposed to be stored on a Mental Number Line (De Hevia, Vallar, & Girelli, 2006; Dehaene, Bossini, & Giraux, 1993; Le Corre & Carey, 2007). Evidence for an ANS includes findings that very young infants are capable of discriminating, representing and remembering particular small numbers of items (Von Aster & Shalev, 2007).

Von Aster and Shalev's (2007) model states that the ANS provides a foundation from which the symbolic number system develops. The symbolic number system is the way in which symbolic numerals are represented in the brain (Carey, 2004; Dehaene, 2011; Le Corre & Carey, 2007; Mussolin, Nys, Content, & Leybaert, 2014) and symbolic number skills are often measured using symbolic number line estimation tasks (Geary, Hoard, Byrd‐Craven, Nugent, & Numtee, 2007; LeFevre et al., 2010; Siegler & Opfer, 2003). The exact process, by which the ANS might give rise to the symbolic number system, is unknown. The ANS Mapping Account, suggests that the ANS is the foundation onto which symbolic representations such as number symbols and number words are mapped (Ansari, 2008; Feigenson et al., 2004; Halberda & Feigenson, 2008; Mundy & Gilmore, 2009; Siegler & Booth, 2004; Von Aster & Shalev, 2007). Alternatively, the Dual Representation View proposes that learning number words and symbols leads to new “exact” numerical representations with exact ordinal content, that are fundamentally distinct from the ANS (Carey, 2004, 2009; Lyons, Ansari, & Beilock, 2012; Piazza, Pica, Izard, Spelke, & Dehaene, 2013; Piazza et al., 2010; Rips, Bloomfield, & Asmuth, 2008).

Regardless of their origins, the ANS and the symbolic number systems are proposed to act in combination as a platform for the development of more complex mathematical skills such as multidigit calculation, word problem solving, algebra, measurement and data handling skills (Barth, La Mont, Lipton, & Spelke, 2005; Butterworth, 1999; Feigenson etal., 2004; Piazza, 2010; Träff, 2013). In support of this, many studies have reported that both the ANS and symbolic number skills, are strong concurrent and longitudinal predictors of general mathematics performance (for examples see: Aunola, Leskinen, Lerkkanen, & Nurmi, 2004; Clarke & Shinn, 2004; Halberda, Mazzocco, & Feigenson, 2008; Hannula, Lepola, & Lehtinen, 2010; Mazzocco, Feigenson, & Halberda, 2011). Based on this theory, this study includes a measure of both ANS and symbolic skills, in addition to a standardized mathematics measures that picks up on more complex mathematical skills including multi‐digit calculation, problem, fractions, etc.

1.2 定义数学思维

与空间思维一样,数学不是一个单一的结构,而是需要多种技能和能力。 本研究使用 Von Aster 和 Shalev(2007)的数字认知模型,该模型假设个体配备了一个与生俱来的核心系统来表示数字,即近似数字系统(ANS)。 ANS 在大脑中存储数值大小的近似表示,没有符号(Cordes、Gelman、Gallistel 和 Whalen,2001;Feigenson、Dehaene 和 Spelke,2004)。 这些表示被建议存储在心智数轴上(De Hevia, Vallar, & Girelli, 2006;Dehaene, Bossini, & Giraux, 1993;Le Corre & Carey, 2007)。 ANS 的证据包括发现非常年幼的婴儿能够辨别、代表和记忆特定的少量物品(Von Aster & Shalev,2007)。

Von Aster 和 Shalev (2007) 的模型指出,ANS 为符号数字系统的发展提供了基础。 符号数字系统是符号数字在大脑中表示的方式(Carey, 2004; Dehaene, 2011; Le Corre & Carey, 2007; Mussolin, Nys, Content, & Leybaert, 2014),并且经常测量符号数字技能 使用符号数轴估计任务(Geary, Hoard, Byrd-Craven, Nugent, & Numtee, 2007; LeFevre et al., 2010; Siegler & Opfer, 2003)。 ANS 产生符号数字系统的确切过程尚不清楚。 ANS 映射帐户表明,ANS 是映射数字符号和数字词等符号表示的基础(Ansari,2008;Feigenson 等,2004;Halberda & Feigenson,2008;Mundy & Gilmore,2009;Siegler & Booth,2004;Von Aster & Shalev,2007)。 或者,双重表示观点提出,学习数字单词和符号会导致新的“精确”数字表示,具有精确的序数内容,这与 ANS 根本不同(Carey,2004,2009;Lyons,Ansari 和 Beilock,2012;Piazza ,Pica、Izard、Spelke 和 Dehaene,2013;Piazza 等人,2010;Rips、Bloomfield 和 Asmuth,2008)。

无论其起源如何,ANS 和符号数字系统都被提议作为一个平台,共同发展更复杂的数学技能,例如多位数计算、文字问题解决、代数、测量和数据处理技能(Barth、La Mont) ,Lipton 和 Spelke,2005 年;Butterworth,1999 年;Feigenson 等人,2004 年;Piazza,2010 年;Träff,2013 年)。 为了支持这一点,许多研究报告称,ANS 和符号数字技能都是一般数学表现的强大的并行和纵向预测因素(例如,参见:Aunola、Leskinen、Lerkkanen 和 Nurmi,2004 年;Clarke 和 Shinn,2004 年; Halberda、Mazzocco 和 Feigenson,2008;Hannula、Lepola 和 Lehtinen,2010;Mazzocco、Feigenson 和 Halberda,2011)。 基于这一理论,本研究包括对 ANS 和符号技能的测量,以及标准化的数学测量,以了解更复杂的数学技能,包括多位数计算、问题、分数等。

1.3 The role of spatial thinking for mathematics

Links between spatial skills (particularly intrinsic‐dynamic skills) and mathematical thinking have been proposed in children as young as 3 years. For example, Verdine et al. (2014) reported that intrinsic‐dynamic spatial skills at age 3 years (as measured using the Test of Spatial Assembly [TOSA]) uniquely predicted 27% of the variation in mathematical problem solving (measured using the Weshler Individual Achievement Test [WIAT]) at age 4 years. Similarly, in slightly older children aged 5 years, intrinsic‐dynamic spatial skills, measured using the Pattern Construction subtest of the British Ability Scales III, were a significant predictor of standardized mathematics performance at age 7, explaining 8.8% of the variation (Gilligan et al., 2017). Similar findings have been reported in crosssectional childhood studies of children from 6 to 8 years, where mental rotation (an intrinsic‐dynamic skill) is significantly associated with performance on both verbal (0.50 < r < 0.63) and non‐verbal calculation tasks (0.40 < r < 0.45) (Hawes et al., 2015).

The previous studies discussed above show a bias towards the use of intrinsic‐dynamic spatial tasks to explore associations between mathematics and spatial skills in primary school children. From a historical perspective, this is unsurprising given that intrinsic‐dynamic spatial skills have repeatedly been associated with STEM outcomes in adult populations (for examples see: Shea et al., 2001; Wai et al., 2009). Insights of the role of the other spatial sub‐domains can be gained from studies of older children. For example, there is evidence from children aged 10 and 11 years, that intrinsic‐static spatial skills (measured using disembedding and matrix reasoning tasks respectively) are significantly correlated with mathematics outcomes (0.37 < r < 0.42) (Markey, 2010; Tosto et al., 2014). Similarly, both intrinsic‐static skills (age 3 years) and performance on composite spatial measures (requiring the use of a range of spatial sub‐domains) at age 7 years, are significant longitudinal predictors of mathematics at approximately 10 years (0.31 < r < 0.49) (Carr et al., 2017; Casey et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2014). These findings suggest that associations between spatial thinking and mathematics in the primary school years may not be limited to the intrinsic‐dynamic spatial domain. However, there is a need to elucidate whether associations are consistent across all spatial and mathematical sub‐domains. Refining the findings in this field would facilitate a better understanding of not just if, but why significant correlations are often reported between mathematics and spatial constructs.

Recent findings from Mix et al. (2016, 2017) provide a first step to this understanding, by investigating performance on an extensive range of spatial and mathematics sub‐domains at 6, 9 and 11 years. In both initial (2016) exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and follow‐up confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (2017) studies, Mix et al. found that although spatial and mathematics tasks are highly correlated, they form distinct factors. Furthermore, by comparing children of differing ages on the same spatial and mathematics tasks, Mix et al. (2016, 2017) provide important evidence that there are distinct relations between individual spatial sub‐domains and mathematics performance, and that these relations vary with age. Intrinsic‐dynamic spatial skills were a significant predictor of mathematics (a general mathematics factor derived from performance on a range of mathematics measures) at 6years only, while Visuo‐Spatial Working Memory (VSWM), measured using a spatial location memory task, was significant at 11 years only. Of note, some cross‐factor loadings reported in the initial EFA were not replicated in the CFA and so these results should be interpreted cautiously (Mix et al., 2016, 2017).

1.3 空间思维在数学中的作用

在先前的研究中,已经提出了3岁儿童的空间技能(特别是内在动态技能)与数学思维之间的联系。例如,Verdine等人(2014年)发现,3岁时使用空间组装测试(TOSA)测量的内在动态空间技能独特地预测了4岁时使用Weshler个体成就测试(WIAT)测量的数学问题解决能力的27%的变异性。类似地,对稍大一些的5岁儿童进行的研究发现,使用英国能力量表III的模式构建子测试测量的内在动态空间技能是7岁时标准化数学表现的重要预测因素,解释了8.8%的变异(Gilligan等人,2017年)。在6至8岁儿童的横断面研究中,也报告了类似的结果,发现心理旋转(一种内在动态技能)与口头计算(0.50 < r < 0.63)和非口头计算任务(0.40 < r < 0.45)的表现显着相关(Hawes等人,2015年)。

先前的研究在探索小学生的数学和空间技能之间的关联时,更偏向于使用内在动态空间任务。从历史的角度来看,这并不令人意外,因为已经多次发现内在动态空间技能与成年人的STEM成果相关(例如Shea等人,2001年;Wai等人,2009年)。通过研究年龄较大的儿童,我们可以了解其他空间子领域的作用。例如,10至11岁儿童的研究发现,使用去嵌入和矩阵推理任务测量的内在静态空间技能与数学成绩显着相关(0.37 < r < 0.42)(Markey,2010年;Tosto等人,2014年)。同样,内在静态技能(3岁)和在7岁时使用复合空间测量的表现(需要使用多个空间子领域)是约10岁时数学的重要纵向预测因子(0.31 < r < 0.49)(Carr等人,2017年;Casey等人,2015年;Zhang等人,2014年)。这些发现表明,小学阶段的空间思维和数学之间的关联可能不仅限于内在动态的空间领域。然而,需要明确这些关联是否在所有空间和数学子领域中保持一致。进一步完善这一领域的研究结果将有助于更好地理解数学和空间结构之间是否存在显著相关性的问题,并解释为什么经常报告显著相关性。

Mix等人(2016年,2017年)的最新发现为我们对空间技能和数学之间关系的理解迈出了第一步。他们通过调查6岁、9岁和11岁儿童在广泛的空间和数学子领域上的表现,进行了初步的探索性因素分析(EFA)和后续的验证性因素分析(CFA)研究。研究结果显示,虽然空间任务和数学任务之间存在高度相关性,但它们形成了不同的因素。

此外,Mix等人(2016年,2017年)通过比较不同年龄儿童在相同的空间和数学任务上的表现,提供了重要的证据,表明个体空间子领域与数学表现之间存在明显的关系,并且这些关系随着年龄的增长而变化。在6岁时,内在动态空间技能被发现是数学(通过一系列数学测量获得的综合数学因素)的重要预测因素,而使用空间位置记忆任务测量的视觉空间工作记忆(VSWM)仅在11岁时显著相关。需要注意的是,初始的EFA中发现的一些因素之间的关联未在CFA中得到复制,因此对这些结果应该谨慎解释(Mix等人,2016年,2017年)。

1.4 Explaining mathematics–spatial associations

The findings outlined above do not support a simple linear coupling between spatial and mathematical cognition. Instead, it has been proposed that several different explanations underpin spatial‐mathematical associations, depending on the mathematical and spatial sub‐domains assessed (Fias & Bonato, 2018). Historically, the Mental Number Line, or the idea that numbers are represented spatially in the brain, was proposed to explain observed associations between spatial and mathematical constructs (Barsalou, 2008; Lakoff & Núñez, 2000). The Spatial‐Numerical Association of Response Codes (SNARC) effect, thought to reflect the presence of the Mental Number Line, has been demonstrated in a number of studies where individuals are faster to respond to small numbers with their left hand and larger numbers with their right hand, suggesting that small numbers are spatially represented to the left and larger numbers are represented to the right in the brain (Dehaene et al., 1993). However, accepting the Mental Number Line as the driver of all spatial–mathematics relations is inconsistent with the differential associations observed between certain spatial and mathematical sub‐domains, as shown by Mix et al. (2016, 2017). Instead, it is now considered that all associations between spatial and mathematical tasks cannot be explained in the same way, and a range of explanations have recently been proposed as theoretical accounts for specific mathematics– spatial relations, explained in detail below.

First, it has been proposed that extrinsic‐static spatial tasks, particularly spatial scaling tasks, rely on proportional reasoning (Newcombe, Möhring, & Frick, 2018). This is explained with reference to two different quantification systems, an extensive system (using absolute amounts) or an intensive system (using proportions or ratios). Accurate spatial scaling between two different sized spaces requires the intensive coding strategy, with proportional mapping of relative, not absolute, distances. This is supported by evidence that spatial scaling performance is correlated with proportional reasoning performance (identification of the strength of flavour of different combinations of cherry juice and water) in children aged 4–5 years (Möhring, Newcombe, & Frick, 2015). In mathematics, similar proportional mapping between discrete (extensive) representations of number to continuous (intensive) representations is required for number line estimation and reasoning about formal fractions (Möhring, Newcombe, Levine, & Frick, 2016; Rouder & Geary, 2014). Theoretically, ANS tasks may require proportional reasoning to facilitate ordinal comparisons between dot arrays (Szkudlarek & Brannon, 2017), while performance on some geometry, area and distance tasks also rely on proportional and not absolute judgements (Barth & Paladino, 2011; Dehaene, Piazza, Pinel, & Cohen, 2003; Slusser, Santiago, & Barth, 2013). Taken together, it is expected that extrinsic‐static spatial task performance will correlate with mathematics tasks that rely on intensive quantity processing or proportional reasoning.

Second, for intrinsic‐dynamic (e.g. mental rotation) and extrinsic‐dynamic spatial tasks (e.g. perspective taking), active processing, including mental visualization and manipulation of objects in space, is thought to be required for successful task completion (Lourenco, Cheung, & Aulet, 2018; Mix et al., 2016). It is postulated that the generation of mental models allows individuals to visualize not only individual components of problems but also the relations between parts of problems (Lourenco et al., 2018). Theoretically, in mathematics, individuals may use mental visualizations to represent and solve complex mathematical word problems (e.g. by visualizing problems in concrete terms, which would allow grouping of visualized constructs and structuring order of operations tasks), or to represent and organize complex mathematical relationships such as multidigit numbers (Huttenlocher, Jordan, & Levine, 1994; Laski et al., 2013; Thompson, Nuerk, Moeller, & Cohen Kadosh, 2013). Mental visualizations may also be used to ground abstract concepts, for example in missing term problems of the format 4 + __ = 5, individuals may use visualizations of blocks or other concrete objects to balance the equation presented (Lourenco et al., 2018). Dynamic spatial tasks are thus expected to correlate with mathematical tasks requiring the mental manipulation or organization of numbers.

Third, intrinsic‐static spatial tasks (e.g. embedded figures) are reliant on form perception, the ability to distinguish shapes from a more complex background or to break pictures that are more complex into parts (Mix et al., 2016). Form perception is theoretically useful for spatial tasks such as map reading and figure drawing (Newcombe & Shipley, 2015). It may also play a role in mathematics tasks such as distinguishing symbols such as + and × symbols, interpreting charts and graphs, and accurately completing multistep calculations which require an understanding of the spatial relations between symbols (Landy & Goldstone, 2007, 2010; Mix et al., 2016). As such intrinsicstatic skills are predicted to relate to mathematics tasks that require identification and use of symbols or visual aids.

1.4 解释数学——空间关联

上述发现并不支持空间认知和数学认知之间的简单线性耦合。 相反,有人提出,根据评估的数学和空间子域,有几种不同的解释支持空间数学关联(Fias & Bonato,2018)。 从历史上看,心理数轴,或者数字在大脑中空间表示的想法,被提出来解释观察到的空间和数学结构之间的关联(Barsalou,2008;Lakoff&Núñez,2000)。 响应码的空间数字关联 (SNARC) 效应被认为反映了心理数轴的存在,这一效应已在许多研究中得到证实,其中个体用左手对小数字作出反应,用左手对大数字作出反应。 右手,这表明在大脑中,较小的数字在空间上表示在左侧,而较大的数字在空间上表示在右侧(Dehaene et al., 1993)。 然而,接受心理数轴作为所有空间数学关系的驱动因素与在某些空间和数学子域之间观察到的差异关联不一致,如 Mix 等人所示。 (2016、2017)。 相反,现在人们认为空间和数学任务之间的所有关联都不能以相同的方式解释,并且最近提出了一系列解释作为特定数学-空间关系的理论解释,下面将详细解释。

首先,有人提出,外在静态空间任务,特别是空间缩放任务,依赖于比例推理(Newcombe、Möhring 和 Frick,2018)。 这是参考两种不同的量化系统来解释的,即广泛的系统(使用绝对量)或密集的系统(使用比例或比率)。 两个不同大小的空间之间的精确空间缩放需要密集的编码策略,以及相对距离而不是绝对距离的比例映射。 有证据表明,4-5 岁儿童的空间尺度表现与比例推理表现(识别樱桃汁和水的不同组合的风味强度)相关(Möhring、Newcombe 和 Frick,2015)。 在数学中,数轴估计和形式分数推理需要数字的离散(广泛)表示与连续(密集)表示之间类似的比例映射(Möhring、Newcombe、Levine 和 Frick,2016 年;Rouder 和 Geary,2014 年)。 理论上,ANS 任务可能需要比例推理来促进点阵列之间的顺序比较(Szkudlarek & Brannon,2017),而某些几何、面积和距离任务的性能也依赖于比例而非绝对判断(Barth & Paladino,2011;Dehaene, Piazza、Pinel 和 Cohen,2003 年;Slusser、Santiago 和 Barth,2013 年)。 综上所述,预计外在静态空间任务表现将与依赖密集数量处理或比例推理的数学任务相关。

其次,对于内在动态(例如心理旋转)和外在动态空间任务(例如透视),主动处理,包括心理可视化和空间中物体的操纵,被认为是成功完成任务所必需的(Lourenco,Cheung, & Aulet,2018;Mix 等人,2016)。 据推测,心理模型的生成不仅可以使个体可视化问题的各个组成部分,还可以可视化问题各部分之间的关系(Lourenco et al., 2018)。 理论上,在数学中,个人可以使用心理可视化来表示和解决复杂的数学文字问题(例如,通过用具体术语可视化问题,这将允许对可视化结构进行分组并构建操作任务的顺序),或者表示和组织复杂的数学关系 例如多位数字 (Huttenlocher, Jordan, & Levine, 1994; Laski et al., 2013; Thompson, Nuerk, Moeller, & Cohen Kadosh, 2013)。 心理可视化也可用于奠定抽象概念,例如在格式 4 + __ = 5 的缺失项问题中,个人可以使用块或其他具体对象的可视化来平衡所呈现的方程(Lourenco 等人,2018)。 因此,动态空间任务预计与需要心理操作或数字组织的数学任务相关。

第三,内在静态空间任务(例如嵌入图形)依赖于形式感知、从更复杂的背景中区分形状或将更复杂的图片分解成多个部分的能力(Mix et al., 2016)。 理论上,形状感知对于地图阅读和图形绘制等空间任务很有用(Newcombe & Shipley,2015)。 它还可以在数学任务中发挥作用,例如区分 + 和 × 符号等符号、解释图表和图形

1.5 Current study

This is the first study to explore associations between different aspects of spatial and mathematical thinking across five consecutive age groups in the primary school years (age 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 years). Based on the theoretical explanations for specific spatial–mathematics relations outlined above (proportional reasoning, mental visualization and form perception), the a priori prediction for this study is that certain spatial sub‐domains will be differentially associated with mathematics outcomes, across all age groups. It is also hypothesized that some spatial–mathematics associations are age‐dependent. Previous studies suggest a developmental transition in the spatial skills that are important for mathematics, which is proposed to occur in middle childhood (Mix et al., 2016, 2017). The inclusion of consecutive age groups in this study provides strong acuity of this developmental change.

1.5 目前的研究

这是第一项探索小学连续五个年龄段(6、7、8、9 和 10 岁)空间思维和数学思维不同方面之间关联的研究。 基于上述对特定空间-数学关系的理论解释(比例推理、心理可视化和形式感知),本研究的先验预测是,某些空间子域将与所有年龄段的数学结果存在差异性关联 。 还假设一些空间数学关联与年龄有关。 先前的研究表明,对数学很重要的空间技能的发展转变被认为发生在童年中期(Mix et al., 2016, 2017)。 这项研究中连续年龄组的纳入提供了对这种发育变化的强烈敏锐度。

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2 材料和方法

2.1 Participants

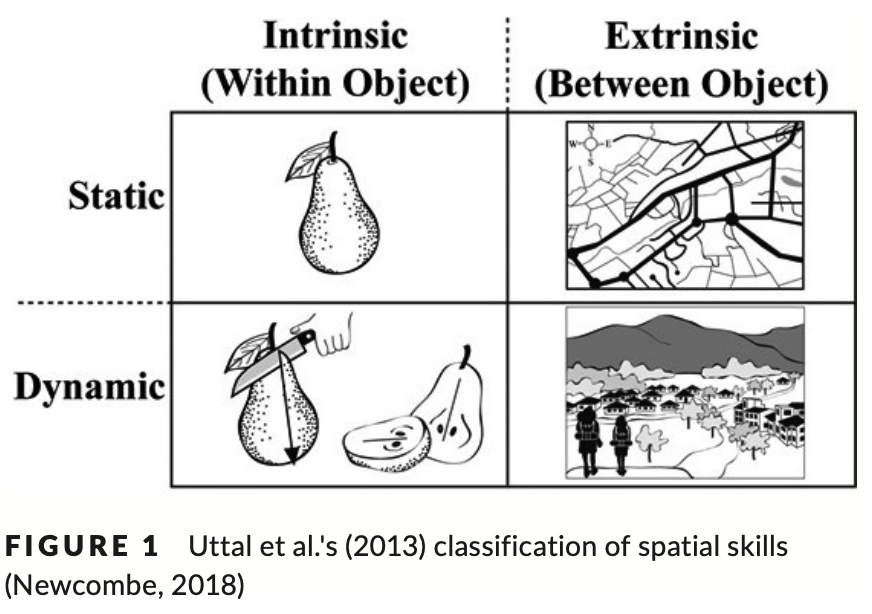

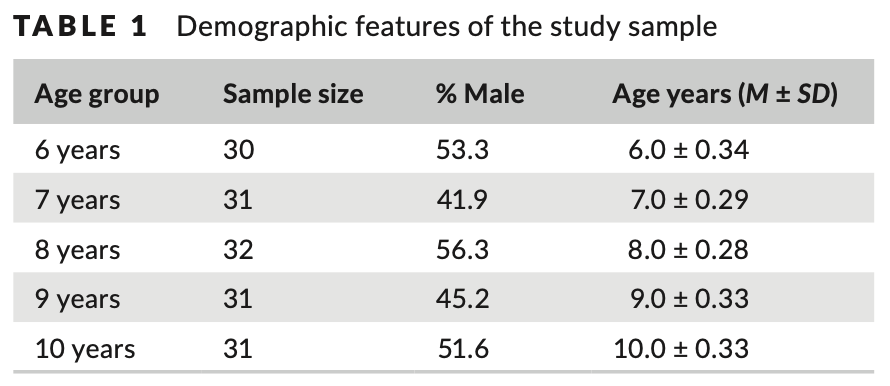

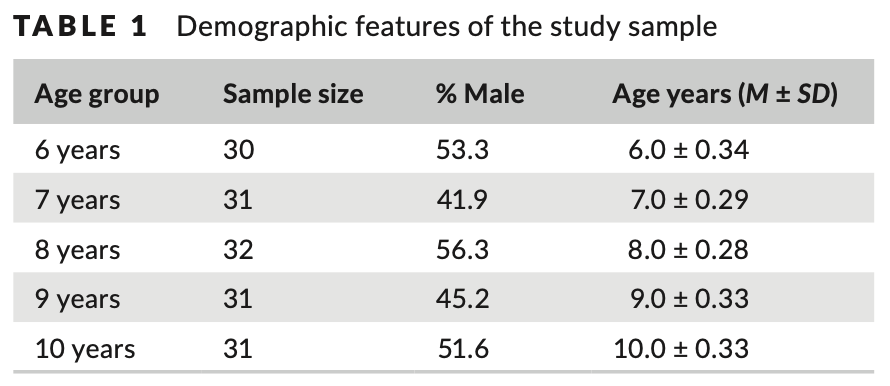

This study included 155 children across five age groups. Participants were drawn from a culturally diverse, London‐based school with a 19% eligibility for free school meals (slightly above the national average of 11% (Department of Education, 2017)). The age and gender of participants in the study are shown in Table 1

2.1 参与者

这项研究包括五个年龄段的 155 名儿童。 参与者来自伦敦一所文化多元化的学校,其中 19% 的人有资格享受免费校餐(略高于 11% 的全国平均水平(教育部,2017 年))。 研究参与者的年龄和性别如表1所示

2.2 Spatial measures

2.2 空间测量

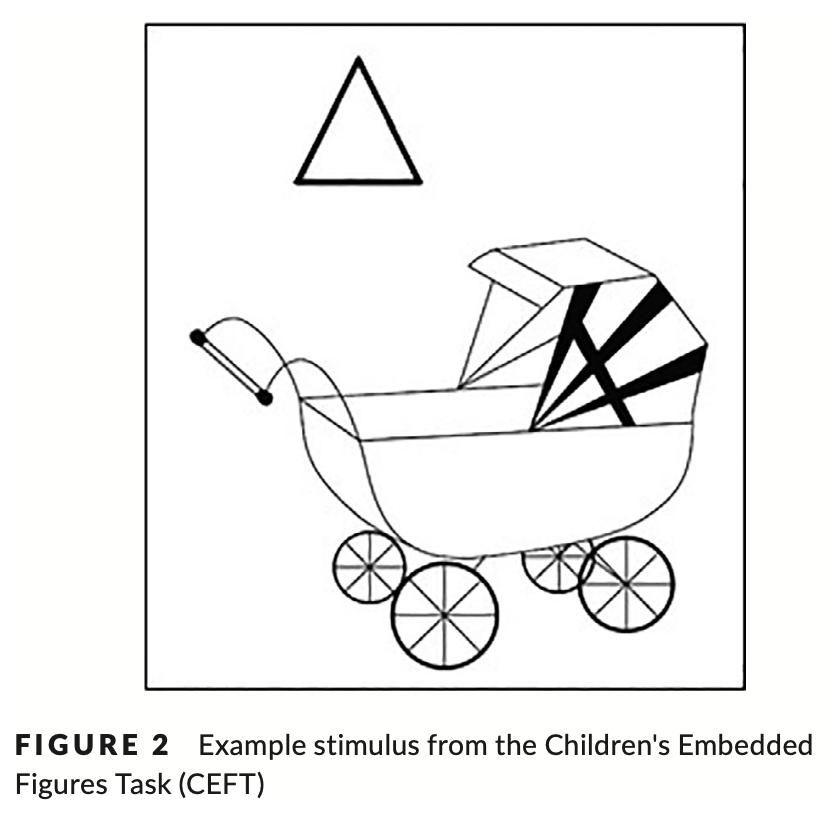

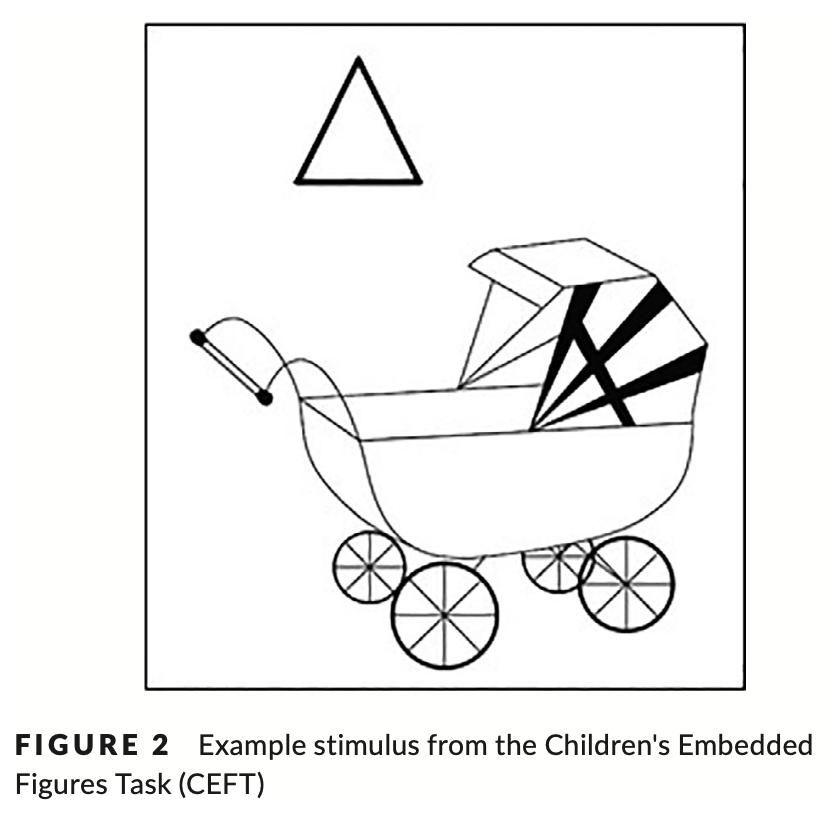

2.2.1 Intrinsic‐static – Children's Embedded Figures Task

The Children's Embedded Figures Task (CEFT) is a measure of intrinsic‐static spatial ability and measures the ability to disembed information from a larger context (Witkin, Otman, Raskin, & Karp, 1971). The task was delivered as per the administration guidelines (Witkin et al., 1971). Participants were required to locate a target shape embedded within a more complex, meaningful picture. The task was presented as two blocks in a fixed order. Within each block, participants were introduced to a reference target shape (house and tent shape for Blocks A and B respectively). For each block, participants first completed four discrimination trials during which they were required to identify the target shape from a selection of other similar shapes. Discrimination trials were repeated until participants correctly answered two items in succession. Following this, participants completed two practice trials (Block A) or a single practice trial (Block B) in which they were required to locate the target shape within a series of more complex pictures and to outline the target shape with their finger (Figure 2). Performance feedback was given for practice trials. Participants repeated each practice trial until successfully locating the target shape. Practice trials were followed by 11 and 14 experimental trials, for Block A and Block B respectively. As for practice trials, participants were required to locate the target shape within more complex pictures. No feedback was given for experimental trials. Only participants failing all trials in Block A, did not progress to Block B. The task finished when participants failed five consecutive trials within Block B. Performance was measured as percentage of correct trials.

2.2.1 内在静态——儿童嵌入图形任务

儿童嵌入图形任务(CEFT)是对内在静态空间能力的衡量,衡量从更大的背景中提取信息的能力(Witkin、Otman、Raskin 和 Karp,1971)。 该任务是根据管理指南交付的(Witkin 等,1971)。 参与者需要找到嵌入更复杂、更有意义的图片中的目标形状。 该任务以固定顺序呈现为两个块。 在每个区块内,向参与者介绍了参考目标形状(分别为 A 区和 B 区的房屋和帐篷形状)。 对于每个块,参与者首先完成四次辨别试验,在此期间他们被要求从其他相似形状的选择中识别出目标形状。 重复歧视试验,直到参与者连续正确回答两个问题。 随后,参与者完成了两次练习试验(A 组)或一次练习试验(B 组),其中要求他们在一系列更复杂的图片中定位目标形状,并用手指勾勒出目标形状(图 2) )。 为实践试验提供了绩效反馈。 参与者重复每次练习试验,直到成功找到目标形状。 实践试验之后,A 组和 B 组分别进行了 11 次和 14 次实验试验。 至于练习试验,参与者需要在更复杂的图片中找到目标形状。 没有给出实验性试验的反馈。 只有在 A 组中所有试验均失败的参与者才不会进入 B 组。当参与者在 B 组中连续五次试验失败时,任务完成。表现以正确试验的百分比来衡量。

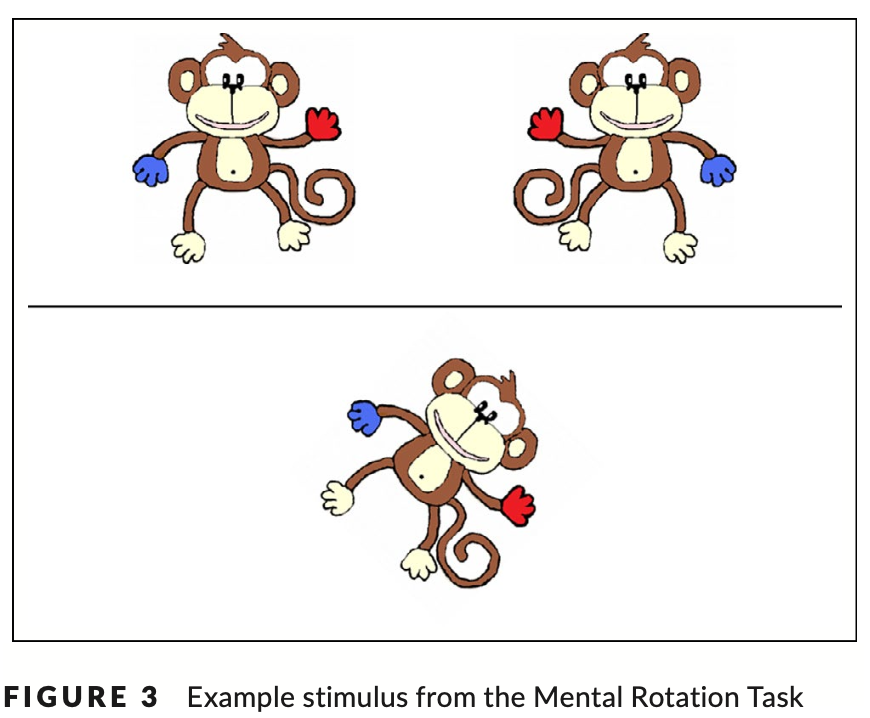

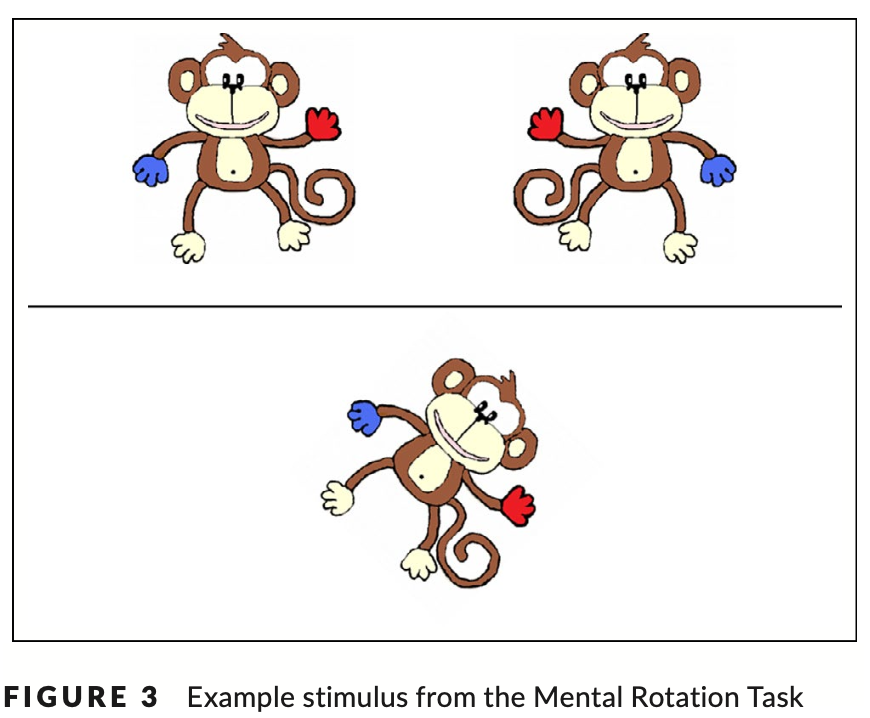

2.2.2 Intrinsic‐dynamic – Mental Rotation Task

The Mental Rotation Task was included as a measure of intrinsicdynamic spatial ability. The protocol and stimuli were modified from Broadbent, Farran, and Tolmie (2014). In each trial, participants were asked to identify which of two monkey images located above a horizontal line, matched the target monkey image below the line. As shown in Figure 3, the images above the line included a mirror image of the target image, and a version of the target image rotated by a fixed degree from the target image. Participants completed four practice trials at 0° followed by 36 experimental trials. Only participants achieving at least 50% in the practice trials were deemed to understand the task instructions and continued to the experimental trials. Experimental trials were randomly presented and included equal numbers of clockwise and anti‐clockwise rotations at 45°, 90° and 135° (eight trials for each degree of rotation), eight trials at 180° and four trials at 0°. Participants used labelled keys on the left and right of the computer keyboard to respond. Percentage accuracy was recorded.

2.2.2 内在动力 – 心理旋转任务

心理旋转任务被纳入作为内在动力空间能力的衡量标准。 方案和刺激由 Broadbent、Farran 和 Tolmie (2014) 修改。 在每次试验中,参与者被要求识别位于水平线上方的两张猴子图像中的哪一张与该线下方的目标猴子图像相匹配。 如图3所示,线上方的图像包括目标图像的镜像以及目标图像从目标图像旋转固定角度的版本。 参与者完成了 4 项 0° 练习试验,随后完成了 36 项实验试验。 只有在练习试验中达到至少 50% 的参与者才被视为理解任务说明并继续进行实验试验。 实验试验是随机进行的,包括相同次数的顺时针和逆时针旋转 45°、90° 和 135°(每个旋转度数八次试验)、八次 180° 试验和四次 0° 试验。 参与者使用计算机键盘左侧和右侧标记的按键进行响应。 记录准确率百分比。

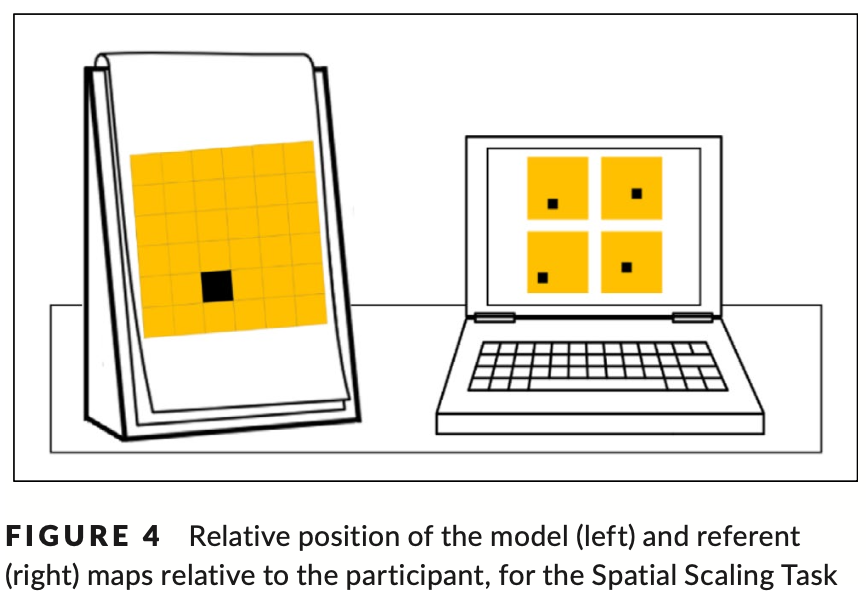

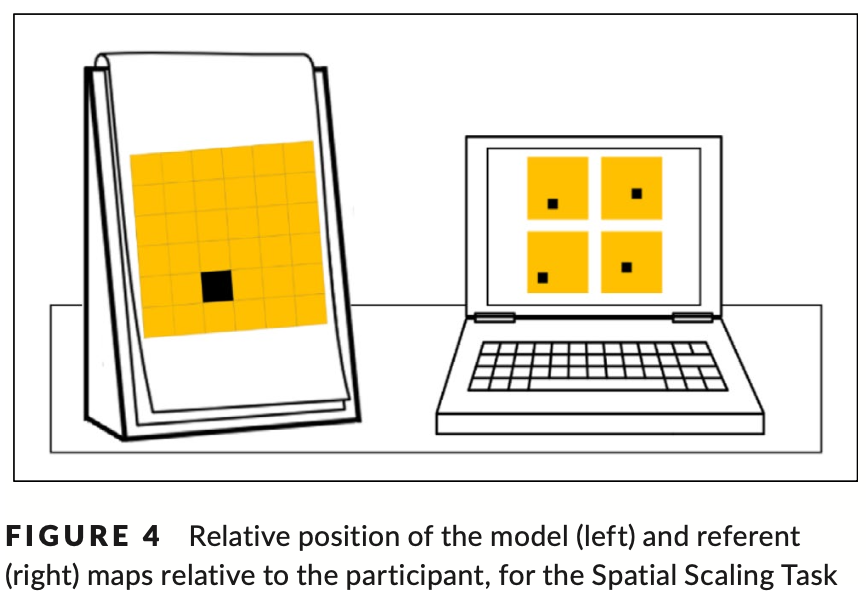

2.2.3 Extrinsic‐static – Scaling Task

A spatial scaling discrimination task was included as an extrinsic‐static task, for use in this study (Gilligan, Hodgkiss, Thomas, & Farran, 2018). As shown in Figure 4, participants were required to use a model “Pirate map” with a target, to identify a corresponding on‐screen referent map from four options (one correct and three distractor maps). Participants responded by manually pressing their answer on a touchscreen laptop. The scaling factor in each trial was determined as the difference in the relative size of the referent and model maps with respect to the participant. The task was presented as three blocks of six experimental trials preceded by two practice trials (scaling factor of 1). Feedback was given for practice trials. If incorrect, participants were asked to repeat the trial until the correct answer was selected. Only participants correctly answering at least one of the two practice items on their first attempt, continued to the experimental blocks. Scaling factor varied by experimental block and was set at 1, 0.5 and 0.25 (i.e. the referent maps were, the same size, one half the size, and one quarter the size of the model map, relative to the participant). Blocks were presented in order of increasing scaling factor. Visual acuity also differed across trials. Within each block, the overall area of the maps, and by extension the scaling factor, did not change. However, half of the trials in each block were presented using a 6 × 6 square grid (requiring gross level acuity) while half were presented using a 10 × 10 square grid (requiring fine level acuity). Percentage accuracy was recorded.

2.2.3 外部静态 – 扩展任务

空间尺度辨别任务被作为外在静态任务纳入本研究中(Gilligan、Hodgkiss、Thomas 和 Farran,2018)。 如图 4 所示,参与者需要使用带有目标的“海盗地图”模型,从四个选项(一张正确地图和三张干扰地图)中识别出相应的屏幕参考地图。 参与者通过在触摸屏笔记本电脑上手动按下答案来进行回答。 每个试验中的比例因子被确定为参照物和模型图相对于参与者的相对大小的差异。 该任务分为三部分,每部分六次实验试验,然后进行两次实践试验(比例因子为 1)。 给出了实践试验的反馈。 如果不正确,参与者被要求重复试验,直到选择正确的答案。 只有参与者在第一次尝试时正确回答两个练习项目中的至少一个,才能继续进行实验。 比例因子因实验块而异,设置为 1、0.5 和 0.25(即相对于参与者,参考图的大小与模型图的大小相同、一半大小和四分之一)。 块按比例因子递增的顺序呈现。 不同试验的视力也存在差异。 在每个块内,地图的整体面积以及扩展的比例因子都没有改变。 然而,每个组中的一半试验使用 6 × 6 方形网格(需要粗级敏锐度)呈现,而一半试验使用 10 × 10 方形网格(需要精细级敏锐度)呈现。 记录准确率百分比。

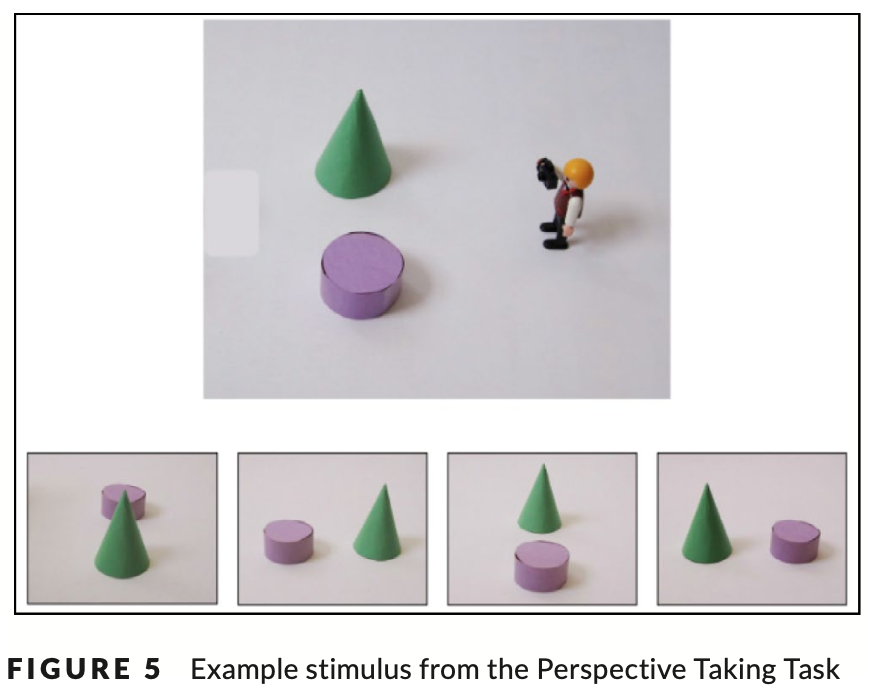

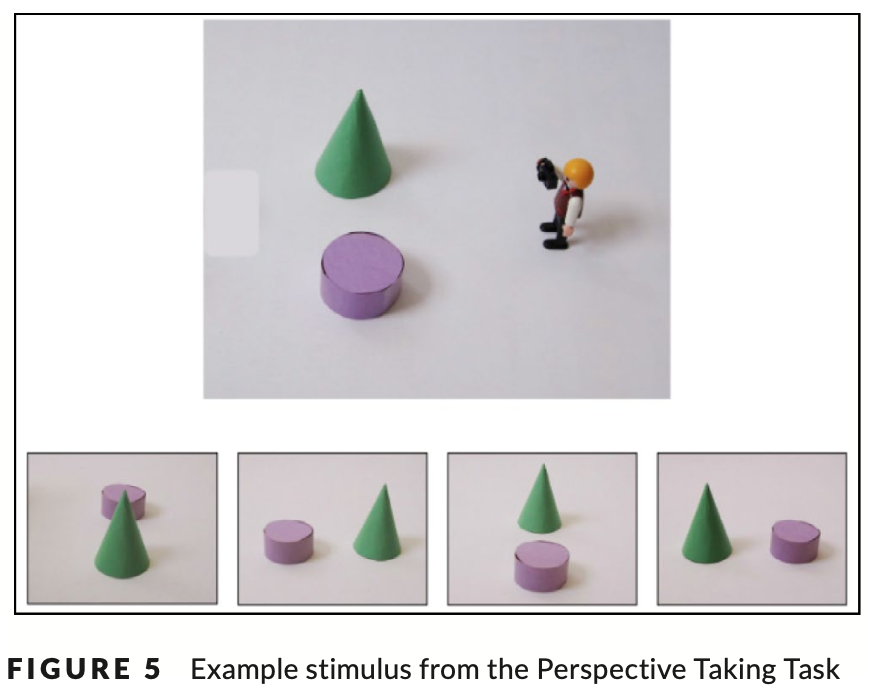

2.2.4 Extrinsic‐dynamic – Perspective Taking Task

The Perspective Taking Task was included as a measure of extrinsic‐dynamic spatial thinking and was taken from Frick, Mohring, and Newcombe (2014). Participants were required to identify which of four photographs had been taken from the perspective of a photographer, based on a 3‐D or pictorial representation of the photographer in an arrangement (Figure5). Participants completed four practice trials with real, 3‐D objects and Playmobil characters holding cameras (to denote photographers). Feedback was given for practice trials and participants were required to successfully answer all practice trials before moving to the 18 computer‐based experimental trials. For experimental trials, complexity was introduced by increasing the number of objects in the stimulus picture (one, two or four objects). Trials also differed in the angular difference between the participant and the photographer. Participants completed equal numbers of trials in which they were positioned at 0°, 90° and 180° from the photographer respectively. The order of presentation of trials was fixed such that the angular difference changed between adjacent trials. In addition, the character acting as a photographer and the objects (colour, shape, relative positions) were also changed between trials. Percentage accuracy was recorded.

2.2.4 外部动力——换位思考任务

观点采择任务被纳入作为外在动态空间思维的衡量标准,取自 Frick、Mohring 和 Newcombe (2014)。 参与者需要根据摄影师在排列中的 3D 或图片表现来识别四张照片中哪一张是从摄影师的角度拍摄的(图 5)。 参与者使用真实的 3D 物体和拿着相机的 Playmobil 角色(代表摄影师)完成了四次练习试验。 为练习试验提供了反馈,参与者需要成功回答所有练习试验,然后才能进行 18 项基于计算机的实验试验。 对于实验试验,通过增加刺激图片中的对象数量(一个、两个或四个对象)来引入复杂性。 试验中参与者和摄影师之间的角度差异也有所不同。 参与者完成了相同数量的试验,其中他们分别位于距摄影师 0°、90° 和 180° 的位置。 试验的呈现顺序是固定的,使得相邻试验之间的角度差异发生变化。 此外,作为摄影师的角色和物体(颜色、形状、相对位置)也在试验中发生变化。 记录准确率百分比。

2.3 Mathematics measures

2.3 数学测量

2.3.1 Mathematics Achievement – NFER Progress in Mathematics Test Series

The National Foundation for Education Research (NFER), Progress in Mathematics (PiM) test series is a standardized measure of mathematics achievement, designed to address the National Mathematics Curriculum in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), 2004). The test series includes items assessing: number; algebra; shape, space and measures; and data handling. Specific, age‐appropriate tests were administered to each age group of participants, as per the test guidelines (NFER, 2004). Age‐based standardized scores with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15, were used in all analyses.

2.3.1 数学成绩——NFER 数学测试系列进展

国家教育研究基金会 (NFER) 数学进展 (PiM) 测试系列是数学成绩的标准化衡量标准,旨在解决英格兰、威尔士和北爱尔兰的国家数学课程问题(国家教育研究基金会 (NFER)、 2004)。 测试系列包括评估项目:数量; 代数; 形状、空间和措施; 和数据处理。 根据测试指南(NFER,2004),对每个年龄组的参与者进行了特定的、适合年龄的测试。 所有分析均使用基于年龄的标准化分数,平均值为 100,标准差为 15。

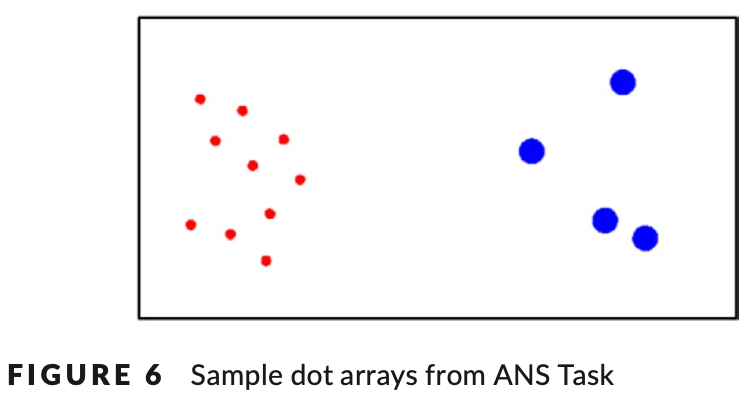

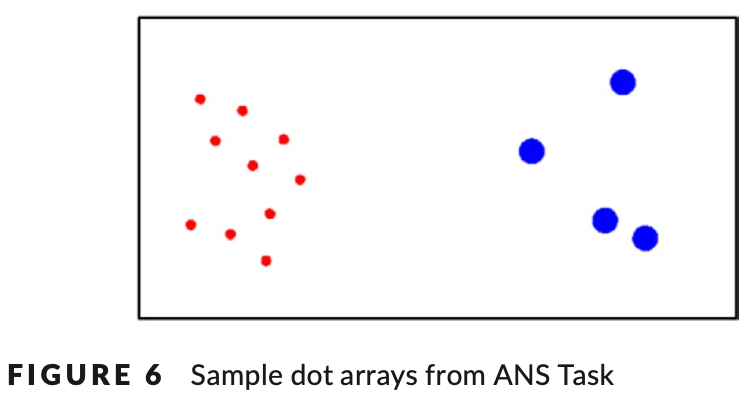

2.3.2 Approximate Number Sense Task

The Approximate Number Sense (ANS) Task used in this study was taken from Gilmore, Attridge, De Smedt, and Inglis (2014). In each trial, participants were required to compare and identify the more numerous of two dot arrays (shown in Figure 6). Each set of dot arrays was presented for 1500 ms (or until a key press) and was followed by a fixation dot. Participants used labelled keys on the left and right of the computer keyboard to respond. Only participants who achieved at least 50% on the practice trials (eight trials) continued to the 64 randomly presented experimental trials. The quantity of dots in each comparison array ranged from 5 to 22. The ratio between the dots in each array varied between 0.5, 0.6, 0.7 and 0.8, with approximately equal numbers of trials assessing each of these ratios. The colour of the more numerous array (red or blue) in addition to the size and the density of dot presentation were counterbalanced between trials. Task performance was measured as percentage accuracy.

2.3.2 近似数感任务

本研究中使用的近似数感 (ANS) 任务取自 Gilmore、Attridge、De Smedt 和 Inglis (2014)。 在每次试验中,参与者都需要比较和识别数量较多的两个点阵列(如图 6 所示)。 每组点阵列呈现 1500 毫秒(或直到按下按键),然后是一个固定点。 参与者使用计算机键盘左侧和右侧标记的按键进行响应。 只有在练习试验(八项试验)中取得至少 50% 成绩的参与者才能继续参加 64 项随机呈现的实验试验。 每个比较阵列中的点数量范围为 5 至 22。每个阵列中的点之间的比率在 0.5、0.6、0.7 和 0.8 之间变化,评估每个比率的试验数量大致相等。 除了点呈现的大小和密度之外,更多阵列的颜色(红色或蓝色)在试验之间进行平衡。 任务绩效以准确率百分比来衡量。

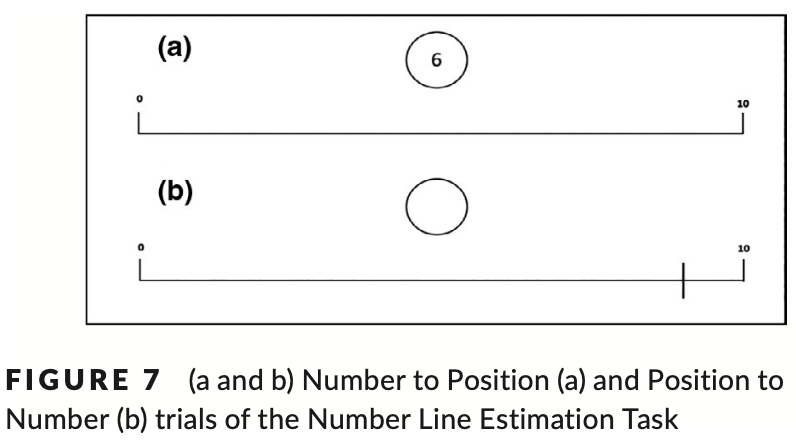

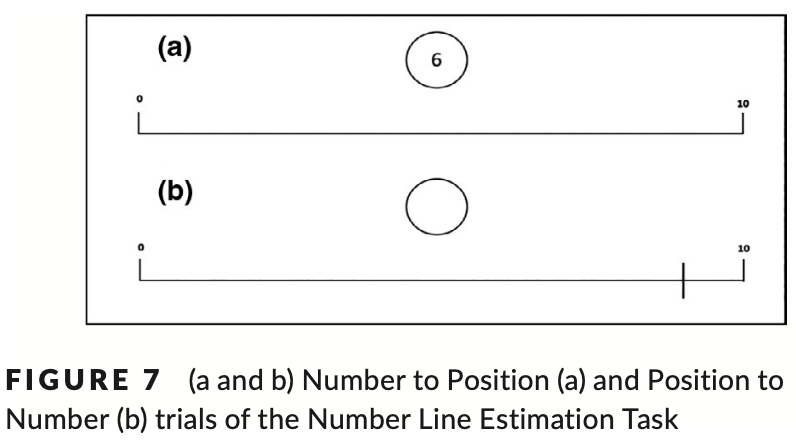

2.3.3 Number Line Estimation Task

The Number Line Estimation Task used to assess numerical representation in this study, was adapted from Siegler and Opfer (2003). Two trial types were included, number estimation (NP) and position estimation (PN) trials. As shown in Figure 7a, for NP trials, participants were presented with a target number and were asked to estimate its location on a number line by drawing a straight line (hatch mark) through the number line at their selected location. As shown in Figure 7b, for PN trials participants were presented with a vertical hatch mark on a number line and were asked to estimate what number was represented by the mark. To reduce floor effects in younger children, and ceiling effects in older children, this task was comprised of three blocks. Within each block, participants completed two practice trials (one NP and one PN) followed by eight experimental trials (equal numbers of NP and PN trials presented alternately). Performance on NP and PN trials were collapsed across blocks. Blocks differed in the number line range presented. As per the Siegler and Opfer (2003) method, the number line in Block B ranged from 0 to 100 and the number line in Block C ranged from 0 to 1,000. Block A with a range of 0–10 was added to reduce floor effects in younger children who may be less familiar with larger numbers.

Trial order was fixed and increased in difficulty. The numbers included in each block were chosen to enhance the identification of children's use of logarithmic and linear models and to minimize the impact of content knowledge (e.g. 25 is one quarter of 100). Similar to other studies, there was over‐sampling of numbers below 20 (Friso‐van den Bos et al., 2015; Laski & Siegler, 2007). Participants were given the opportunity to complete all blocks. However, the 0–10 block was considered an age‐specific measure, and was analysed, at 6 and 7 years only. One measure of performance was Percentage Absolute Error (PAE). PAE is the numerical distance from a participant's answer to the correct answer, divided by the length of the number line. This measure reflects the accuracy of participants’ estimates. Linear response patterns (R2LIN) were also calculated for each block by completing curve estimation for each participant, based on the correlation between participants’ estimates and the target numbers. Linear response patterns indicate the degree to which a participant's estimates are linearly spread across the number line. PAE and linear response patterns for each block were subsequently used as the outcome variables in all analysis (six mathematics outcome variables), as both measures provide distinct information on numerical representations (Simms, Clayton, Cragg, Gilmore, & Johnson, 2016).

Across all blocks where a participant's mean PAE scores for the practice trials in a block were greater than 15%, or where participants who failed to answer at least 80% of items in a block, they were excluded from analysis for this block. For the 0–1,000 block, only four children aged 6 years were eligible for inclusion, hence this age group was excluded from analysis. For the Number Line Estimation Task, all results reported are based on R2LIN values. Similar patterns of performance, with smaller effects, were found for PAE scores (see supplementary material).

2.3.3 数轴估计任务

本研究中用于评估数值表示的数轴估计任务改编自 Siegler 和 Opfer (2003)。 包括两种试验类型:数量估计(NP)和位置估计(PN)试验。 如图 7a 所示,对于 NP 试验,向参与者提供了一个目标数字,并要求参与者通过在所选位置的数轴上画一条直线(阴影线)来估计其在数轴上的位置。 如图 7b 所示,对于 PN 试验,参与者在数轴上看到一个垂直影线标记,并被要求估计该标记代表什么数字。 为了减少年幼儿童的地板效应和年龄较大儿童的天花板效应,这项任务由三个部分组成。 在每个模块中,参与者完成了两项练习试验(一项 NP 和一项 PN),然后是八项实验性试验(交替呈现相同数量的 NP 和 PN 试验)。 NP 和 PN 试验的表现在各组中崩溃。 块的不同之处在于所呈现的数轴范围。 根据 Siegler 和 Opfer (2003) 方法,B 块中的数轴范围为 0 到 100,C 块中的数轴范围为 0 到 1,000。 添加范围为 0-10 的 A 块是为了减少对较大数字不太熟悉的年幼儿童的地板效应。

试炼顺序固定,难度增加。 选择每个块中包含的数字是为了增强对儿童使用对数和线性模型的识别,并尽量减少内容知识的影响(例如,25 是 100 的四分之一)。 与其他研究类似,对 20 以下的数字进行了过度采样(Friso-van den Bos 等人,2015 年;Laski 和 Siegler,2007 年)。 参与者有机会完成所有区块。 然而,0-10 区块被认为是一种特定年龄的衡量标准,并且仅在 6 岁和 7 岁时进行了分析。 衡量性能的一项指标是百分比绝对误差 (PAE)。 PAE 是从参与者的答案到正确答案的数字距离除以数轴长度。 该指标反映了参与者估计的准确性。 基于参与者的估计和目标数字之间的相关性,还通过完成每个参与者的曲线估计来计算每个块的线性响应模式(R2LIN)。 线性响应模式表明参与者的估计在数轴上线性分布的程度。 每个模块的 PAE 和线性响应模式随后被用作所有分析中的结果变量(六个数学结果变量),因为这两种度量都提供了有关数值表示的不同信息(Simms、Clayton、Cragg、Gilmore 和 Johnson,2016)。

在所有块中,如果参与者在一个块中的练习试验的平均 PAE 分数大于 15%,或者参与者未能回答块中至少 80% 的项目,则他们被排除在该块的分析之外。 对于 0-1,000 组,只有 4 名 6 岁儿童符合纳入条件,因此该年龄组被排除在分析之外。 对于数轴估计任务,报告的所有结果均基于 R2LIN 值。 PAE 分数也有类似的表现模式,但影响较小(参见补充材料)。

2.4 Other measures

2.4 其他措施

2.4.1 British Picture Vocabulary Scale (BPVS)

To control for verbal ability, the British Picture Vocabulary Scale (III), a measure of receptive vocabulary, was administered (Dunn, Dunn, Styles, & Sewell, 2009). Given that vocabulary is highly correlated with IQ (Sattler, 1988), the BPVS‐III also acted as an estimate of general IQ. As per the administration guidelines, participants were asked to select which of four coloured pictures best illustrated the meaning of a given word.

2.4.1 英国图片词汇量表(BPVS)

为了控制言语能力,采用了英国图片词汇量表 (III),这是一种接受词汇量的衡量标准(Dunn、Dunn、Styles 和 Sewell,2009 年)。 鉴于词汇量与智商高度相关(Sattler,1988),BPVS-III 也可以作为一般智商的估计。 根据管理指南,参与者被要求从四张彩色图片中选择哪一张最能说明给定单词的含义。

2.5 Procedure

Each participant completed the battery of mathematics, spatial and vocabulary measures, across three test sessions. Two further sessions included science measures not reported here (see Hodgkiss, Gilligan, Tolmie, Thomas, & Farran, 2018). Within each session, mathematics tasks were completed prior to spatial tasks in order to avoid mathematics improvements due to spatial training effects (Cheng & Mix, 2014). Beyond this, task order within each session was randomized. During Session 1, a 1‐hr classroom‐based session, a standardized measure of mathematics, the NFER PiM Test and (for children aged 8 years and older) the Number Line Task, were completed. Session 2, a 35‐min session, was completed in the school's computer suite in groups of 8 children, supervised by a minimum of two researchers. For computerized tasks, Hewlett Packard (HP) computers with a screen size of 17 inches were used. Children completed mathematics tasks (the ANS Task, the CMAQ and the Number Line Task [children aged 7 and younger]) and spatial measures (the Mental Rotation Task and a Folding task [not discussed here]). For session 3, participants were tested individually in a quiet room using a 13‐inch HP touchscreen laptop. This session lasted 45 min and included spatial tasks (the Perspective Taking Task, the CEFT and the Scaling Task) and the vocabulary measure (the BPVS).

2.5 程序

每位参与者在三个测试环节中完成了一系列数学、空间和词汇测量。 另外两场会议包括此处未报告的科学措施(参见 Hodgkiss、Gilligan、Tolmie、Thomas 和 Farran,2018)。 在每个会话中,数学任务在空间任务之前完成,以避免由于空间训练效应而导致数学改进(Cheng & Mix,2014)。 除此之外,每个会话中的任务顺序都是随机的。 在第 1 节期间,完成了 1 小时的课堂课程、标准化数学测量、NFER PiM 测试和(针对 8 岁及以上儿童)数轴任务。 第 2 部分为 35 分钟,以 8 名儿童为一组在学校的计算机室中完成,并由至少两名研究人员监督。 对于计算机化任务,使用屏幕尺寸为 17 英寸的惠普 (HP) 计算机。 孩子们完成了数学任务(ANS 任务、CMAQ 和数轴任务 [7 岁及以下的儿童])和空间测量(心理旋转任务和折叠任务 [此处未讨论])。 在第 3 节中,参与者使用 13 英寸 HP 触摸屏笔记本电脑在安静的房间中进行了单独测试。 该会议持续 45 分钟,包括空间任务(透视任务、CEFT 和扩展任务)和词汇量测量(BPVS)。

2.6 Analysis strategy

Due to school absences and technical errors, 10 participants had missing scores for a single task in the battery (the proportion of missing data was 0.7%). Missing data were distributed as follows: the CEFT (one participant); the Perspective Taking Task (two participants); the NFER PiM Test (two participants); the ANS Task (two participants); the Number Line Task (one participant); and the BPVS (two participants). As no individual participant was missing data for more than one task, and to optimize power, missing values were replaced by mean scores on that task for a participant's age group. Parametric analyses were completed as tests of normality indicated that all measures were broadly normal. For all measures, performance across age groups was viewed graphically. For measures in which a ceiling (or floor effect) was suspected, one‐sample t tests were completed against ceiling (or floor) performance. For percentage accuracy scores, floor and ceiling were set at 0% and 100%, respectively. For R2LIN scores, floor and ceiling levels were set at 0 and 0.99, respectively. No significant floor or ceiling effects were found.

Gender differences in spatial and mathematics performance were investigated using Bonferroni adjusted t tests to account for multiple comparisons (alpha levels of 0.004 [0.05/14]). Where Levene's test was violated, the results for unequal variances were reported. Correlations were completed to investigate the relative associations between measures and to inform regression models. Hierarchical regression models were completed for each mathematical outcome, to investigate the proportion of mathematical variation explained by spatial skills, after accounting for other known predictors of mathematical performance including language ability (the BPVS) and age. Gender was included as a control variable for mathematics tasks with which it was significantly correlated.

For regression models, all predictors were converted to zscores prior to entry. The collinearity statistics indicated appropriate Tolerance and VIF scores for all regression models, where a cut off of >0.2 was used for Tolerance scores (Menard, 1995) and a cut off of <10 was used for VIF scores (Myers, 1990). For all models, the control variables were added in Step 1. In Step 2, the spatial measures were entered together, as there was no strong evidence as to which skills might best predict different aspects of mathematical performance. In step 3, interaction terms between age and each spatial skill were added using forward stepwise entry. Only significant interactions were retained in the final models. These significant interactions were further explored using scatterplots. Based on changes in performance patterns across age groups (determined visually from the graphs), the sample was divided into younger and older age groups. Follow‐up regressions were completed with younger and older participants, respectively. For all regression analyses, adjusted r2 values are reported.

The sample size was determined using GPower. Based on previous studies on the role of spatial thinking as a predictor of mathematics, a medium to large effect size was expected (Gilligan et al., 2017: f2 = 0.217). Power analysis was based on the largest possible regression model which included three control variables (age, vocabulary scores and gender), four spatial predictors and four age × spatial task interaction terms. To achieve power of 0.8, 78 participants were required. Due to missing data (described above) for some tasks, the desired participant numbers were not achieved for all models. Post hoc power analysis was completed to determine the achieved power for each model. Except for the 0–10 Number Line Estimation Task, all models achieved a power level greater than 0.91, which is above the suggested power level of 0.8 (Cohen, 1988). The results for the 0–10 Number Line Estimation Task should be interpreted cautiously due to the relatively low power of this model (0.754) (see supplementary material).

2.6 分析策略

由于学校缺勤和技术错误,有 10 名参与者在电池组中的单个任务中缺失了分数(缺失数据的比例为 0.7%)。 缺失数据分布如下:CEFT(一名参与者); 换位思考任务(两名参与者); NFER PiM 测试(两名参与者); ANS 任务(两名参与者); 数轴任务(一名参与者); 和 BPVS(两名参与者)。 由于没有个体参与者缺失超过一项任务的数据,并且为了优化功效,缺失值被参与者年龄组的该任务的平均分数所取代。 参数分析完成后,正态性检验表明所有指标基本正常。 对于所有指标,以图形方式查看跨年龄组的表现。 对于怀疑存在天花板(或地板效应)的措施,针对天花板(或地板)性能完成单样本 t 检验。 对于百分比准确度分数,下限和上限分别设置为 0% 和 100%。 对于 R2LIN 分数,下限和上限水平分别设置为 0 和 0.99。 没有发现明显的地板或天花板效应。

使用 Bonferroni 调整 t 检验来研究空间和数学表现的性别差异,以解释多重比较(α 水平为 0.004 [0.05/14])。 如果违反 Levene 检验,则报告不等方差的结果。 完成相关性是为了调查测量之间的相对关联并为回归模型提供信息。 在考虑了其他已知的数学表现预测因素(包括语言能力(BPVS)和年龄)后,针对每个数学结果完成了层次回归模型,以研究由空间技能解释的数学变异的比例。 性别被列为数学任务的控制变量,与性别显着相关。

对于回归模型,所有预测变量在输入之前都转换为 zscore。 共线性统计表明所有回归模型都有适当的 Tolerance 和 VIF 分数,其中 Tolerance 分数使用 >0.2 的截止值(Menard,1995),VIF 分数使用 <10 的截止值(Myers,1990)。 对于所有模型,控制变量都是在步骤 1 中添加的。在步骤 2 中,一起输入空间测量值,因为没有强有力的证据表明哪些技能可以最好地预测数学表现的不同方面。 在步骤 3 中,使用前向逐步输入添加年龄和每个空间技能之间的交互项。 最终模型中只保留了显着的交互作用。 使用散点图进一步探讨了这些重要的相互作用。 根据不同年龄组表现模式的变化(从图表中直观地确定),样本被分为年轻组和老年组。 分别对年轻和年长的参与者完成了后续回归。 对于所有回归分析,都会报告调整后的 r2 值。

样本大小是使用 GPower 确定的。 根据之前关于空间思维作为数学预测因子的作用的研究,预计效果大小为中等到大(Gilligan 等人,2017:f2 = 0.217)。 功效分析基于最大可能的回归模型,其中包括三个控制变量(年龄、词汇分数和性别)、四个空间预测变量和四个年龄×空间任务交互项。 为了达到 0.8 的功效,需要 78 名参与者。 由于某些任务缺少数据(如上所述),所有模型均未达到所需的参与者数量。 完成事后功效分析以确定每个模型所达到的功效。 除了 0-10 数轴估计任务外,所有模型的功效水平都大于 0.91,高于建议的功效水平 0.8(Cohen,1988)。 由于该模型的功效相对较低 (0.754),因此应谨慎解释 0-10 数轴估计任务的结果(请参阅补充材料)。

3 RESULTS

3 个结果

3.1 Overall task performance

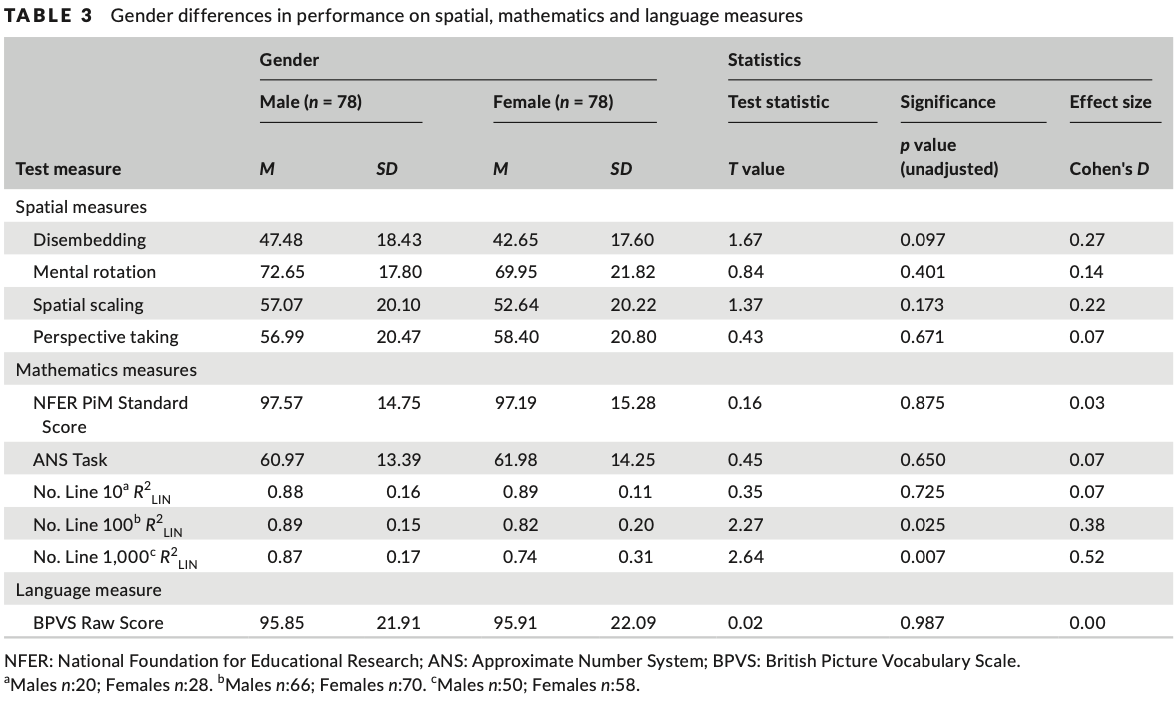

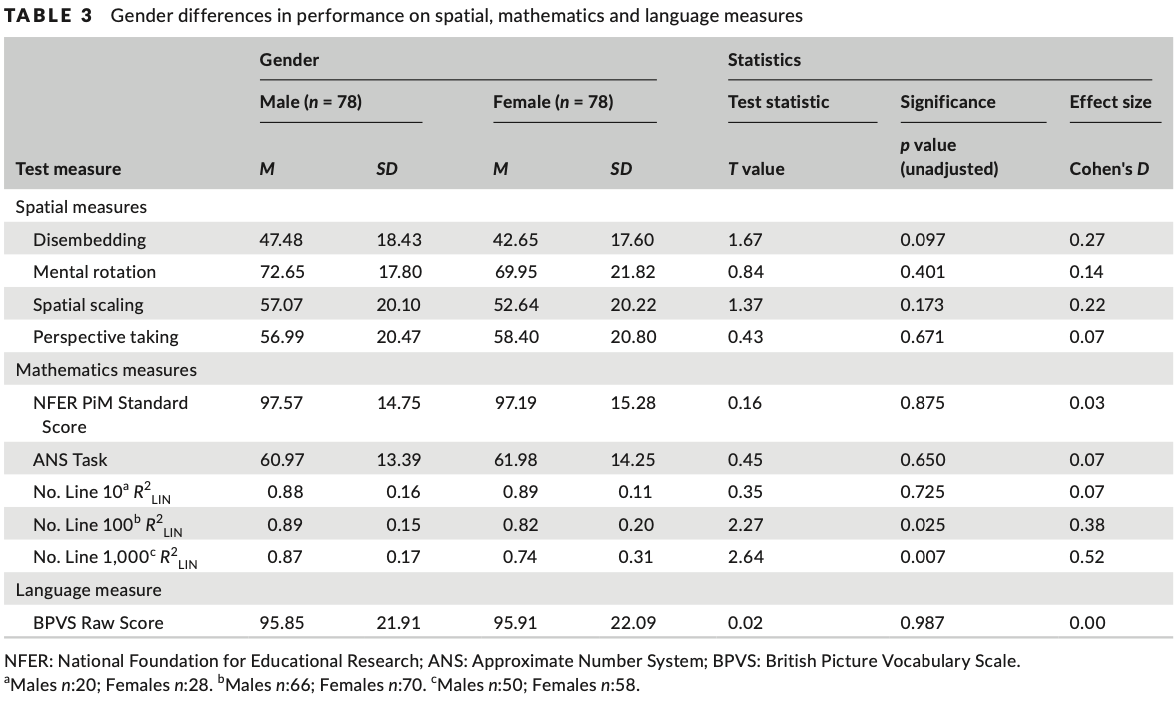

Descriptive statistics across age groups are shown in Table2. Variation in task performance was reported for all measures, with no floor or ceiling effects. Where possible to measure, task performance was above chance across age groups. The only exception to this was 6 year olds’ performance on the ANS task, t (29) = −1.89, p = 0.069, d = −0.35. Given that this might reflect poor ability rather than a poor understanding of the task aims, performance of this group on the ANS task was retained in the analyses. As shown in Table 3, there were no significant gender differences for any of the spatial measures or the BPVS (p > 0.05). For unadjusted p values, significant differences favouring males were reported for both the 0–100 (p = 0.025, d = 0.38) and the 0–1,000 (p = 0.007, d = 0.52) block of the Number Line Estimation Task. These differences were not significant when the results were adjusted for multiple comparisons (alpha level = 0.004). However, to ensure that the influence of gender was not overlooked, gender was included as a control variable in subsequent regression analysis for the 0–100 and 0–1,000 blocks of the Number Line Estimation Task.

3.1 总体任务绩效

各年龄组的描述性统计数据如表2所示。 所有措施均报告了任务绩效的变化,没有下限或上限效应。 在可以测量的情况下,不同年龄组的任务表现都高于机会。 唯一的例外是 6 岁儿童在 ANS 任务中的表现,t (29) = -1.89,p = 0.069,d = -0.35。 鉴于这可能反映了能力较差,而不是对任务目标理解较差,因此该组在 ANS 任务上的表现被保留在分析中。 如表 3 所示,任何空间测量或 BPVS 均不存在显着的性别差异 (p > 0.05)。 对于未调整的 p 值,数轴估计任务的 0-100(p = 0.025,d = 0.38)和 0-1,000(p = 0.007,d = 0.52)块均报告了有利于男性的显着差异。 当对多重比较结果进行调整时,这些差异并不显着(α 水平 = 0.004)。 然而,为了确保性别的影响不被忽视,在数轴估计任务的 0-100 和 0-1,000 块的后续回归分析中,将性别作为控制变量。

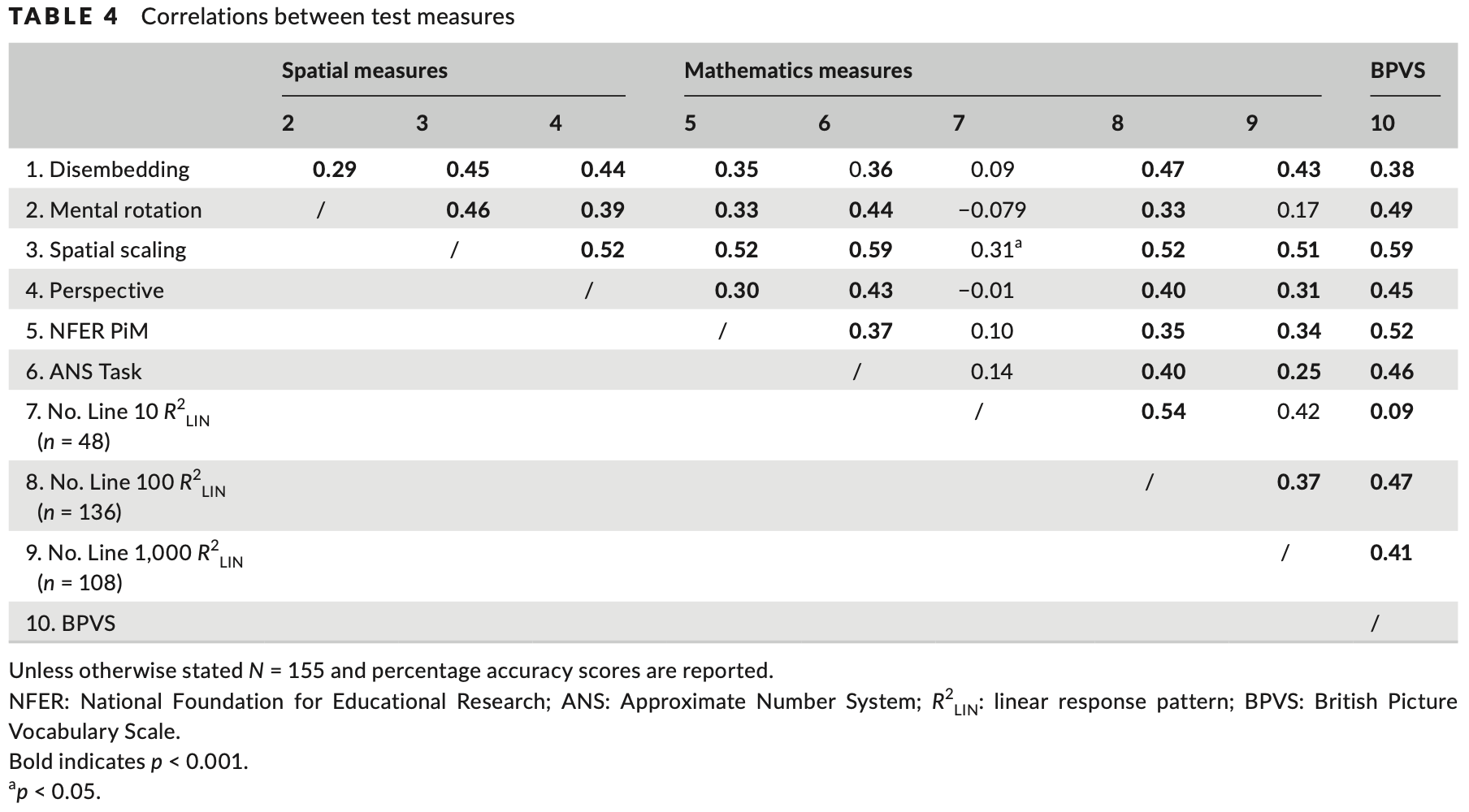

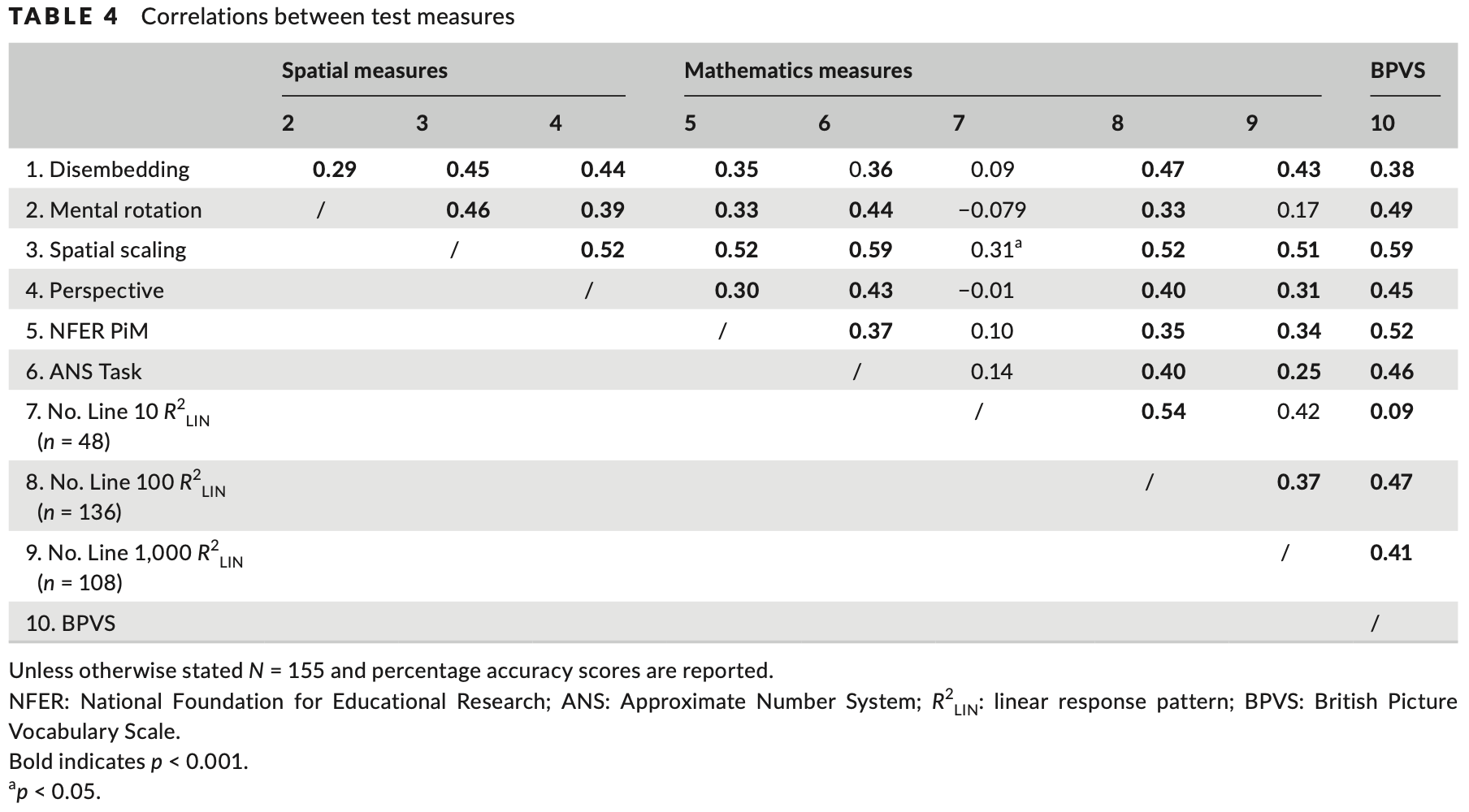

3.2 Associations between task performance on different measures

The results of bivariate correlations between all measures are outlined in Table 4. Significant correlations at the p < 0.001 level were reported between the performance accuracy scores for all spatial measures. For mathematics measures, the NFER PiM test and the ANS Task were significantly correlated with all spatial measures and the BPVS (p < 0.001). The 0–100 and 0–1,000 blocks of the Number Line Estimation Task were significantly correlated with the spatial measures and the BPVS, with the exception that the 0–1,000 task was not correlated with mental rotation (p = 0.080). For the 0–10 block of the Number Line Estimation Task, significant associations were found for spatial scaling (p = 0.034) and the 0–100 block of the Number Line Estimation Task (p < 0.001) only.

3.2 不同指标的任务绩效之间的关联

表 4 概述了所有测量值之间的双变量相关性结果。所有空间测量值的性能准确度得分之间均报告了 p < 0.001 水平的显着相关性。 对于数学测量,NFER PiM 测试和 ANS 任务与所有空间测量和 BPVS 显着相关 (p < 0.001)。 数轴估计任务的 0-100 和 0-1,000 块与空间测量和 BPVS 显着相关,但 0-1,000 任务与心理旋转不相关 (p = 0.080)。 对于数轴估计任务的 0-10 块,仅发现空间缩放 (p = 0.034) 和数轴估计任务的 0-100 块 (p < 0.001) 存在显着关联。

3.3 Identifying predictors of mathematics outcomes

Hierarchical regression models were completed for each mathematical outcome to investigate the proportion of mathematical variation accounted for by spatial skills, after controlling for other known predictors of mathematics. The results reported in Tables 5–95‒9 reflect the regression statistics (b, SE, ß, t and p) for the final models (i.e. when all predictors had been entered).

3.3 确定数学结果的预测因素

在控制了其他已知的数学预测因子后,对每个数学结果完成了层次回归模型,以研究空间技能所造成的数学变异的比例。 表 5-95-9 中报告的结果反映了最终模型(即输入所有预测变量时)的回归统计数据(b、SE、ß、t 和 p)。

3.3.1 Model 1: Identifying predictors of standardized mathematics performance

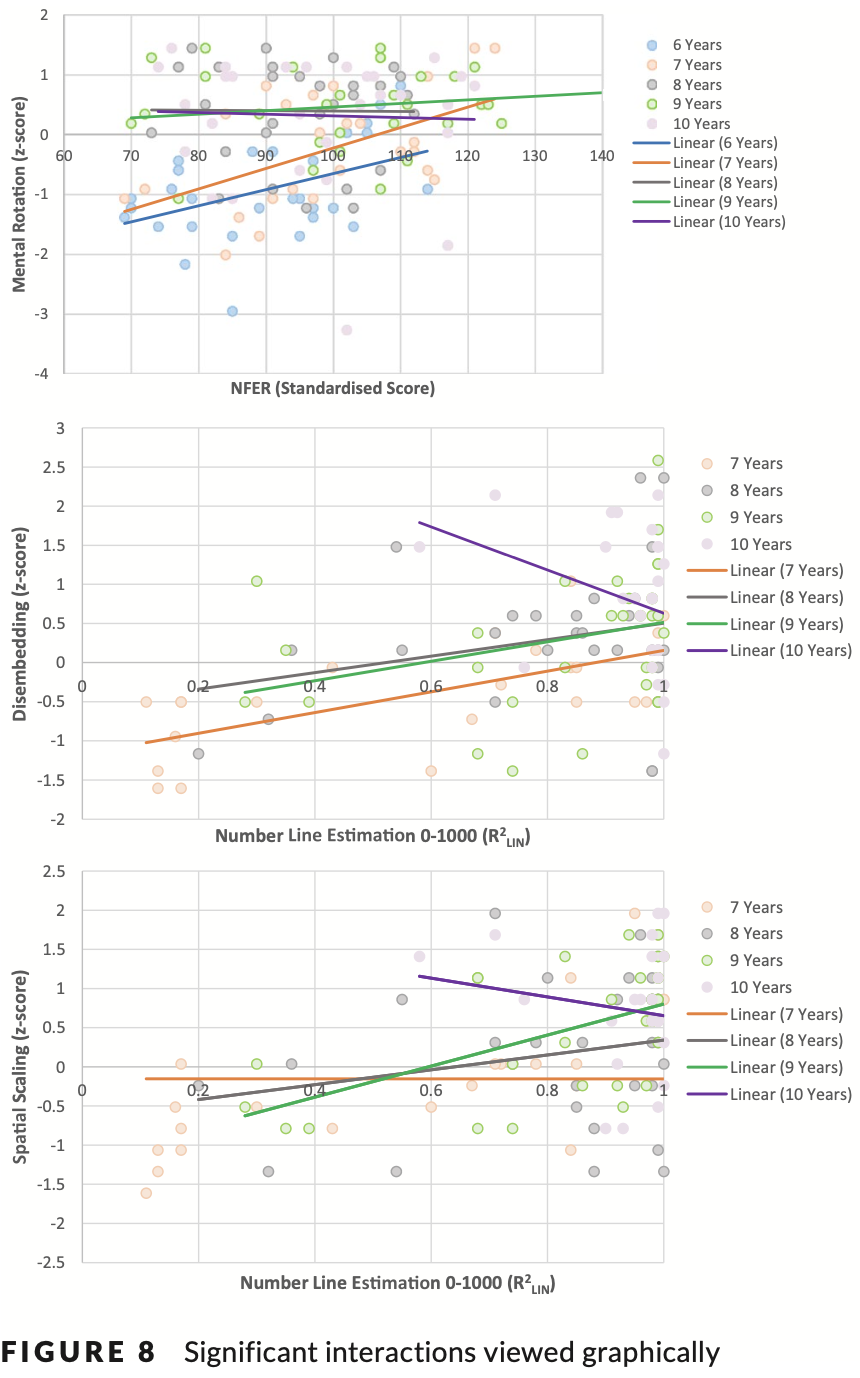

Model 1 sought to determine the contribution of different spatial skills to the variation in standardized mathematics performance, as measured using the NFER PiM test. As shown in Table 5, the final model accounted for 42.6% of the variation in mathematical achievement. In step 1, the control variables including age1 and language ability were added to the model accounting for 28.2% of the variation in standardized mathematics performance. In step 2, the spatial measures were added to the model, uniquely predicting an additional 12.4% of the variation. Finally, in step 3 interaction terms between each spatial skill and age were entered into the model. Only the interaction between mental rotation and age was retained. It accounted for an additional 2.0% of the variation in standardized mathematics performance. Taken together, age, language ability, spatial scaling, disembedding and the interaction term between mental rotation and age, were all significant predictors of mathematics achievement in the final model.

The interaction was explored graphically by plotting standardized mathematics scores against mental rotation scores for each age group (Figure 8). The graph indicated a difference in the relationship between measures at 6 and 7 years compared to 8, 9 and 10 years. The sample was divided accordingly, and the regression analysis was re‐run using younger (6 and 7 years; n = 60) and older groups (8, 9 and 10 years; n = 93), respectively. As shown in Table 5, the patterns reported for both age groups were broadly similar to the overall model, with spatial scaling and disembedding identified as significant predictors in both models. However, for younger participants mental rotation approached significance (p = 0.057) and the β values were similar for mental rotation (β = 0.20) compared to disembedding (β = 0.22) and spatial scaling (β = 0.27). This pattern was not present for the older group, and a non‐significant β value was reported for mental rotation (β = −0.13).

3.3.1 模型 1:识别标准化数学成绩的预测因素

模型 1 试图确定不同空间技能对标准化数学成绩变化的贡献(使用 NFER PiM 测试进行测量)。 如表5所示,最终模型解释了数学成绩变异的42.6%。 在步骤 1 中,包括年龄 1 和语言能力在内的控制变量被添加到模型中,占标准化数学成绩变异的 28.2%。 在步骤 2 中,将空间测量添加到模型中,唯一地预测了额外的 12.4% 的变化。 最后,在步骤 3 中,将每个空间技能和年龄之间的交互项输入到模型中。 仅保留了心理旋转与年龄之间的相互作用。 它额外解释了标准化数学成绩变化的 2.0%。 总的来说,年龄、语言能力、空间尺度、脱嵌以及心理旋转和年龄之间的相互作用项,都是最终模型中数学成绩的重要预测因素。

通过绘制每个年龄组的标准化数学分数与心理旋转分数的关系图,以图形方式探索了这种相互作用(图 8)。 该图显示了 6 年和 7 年测量值之间的关系与 8 年、9 年和 10 年测量值之间的关系存在差异。 对样本进行相应划分,并分别使用年轻组(6 岁和 7 岁;n = 60)和年长组(8、9 和 10 岁;n = 93)重新进行回归分析。 如表 5 所示,两个年龄组报告的模式与整体模型大致相似,空间尺度和脱嵌被认为是两个模型中的重要预测因素。 然而,对于年轻参与者来说,心理旋转接近显着性(p = 0.057),并且与脱嵌(β = 0.22)和空间缩放(β = 0.27)相比,心理旋转(β = 0.20)的β值相似。 老年组不存在这种模式,并且心理旋转的 β 值不显着(β = -0.13)。

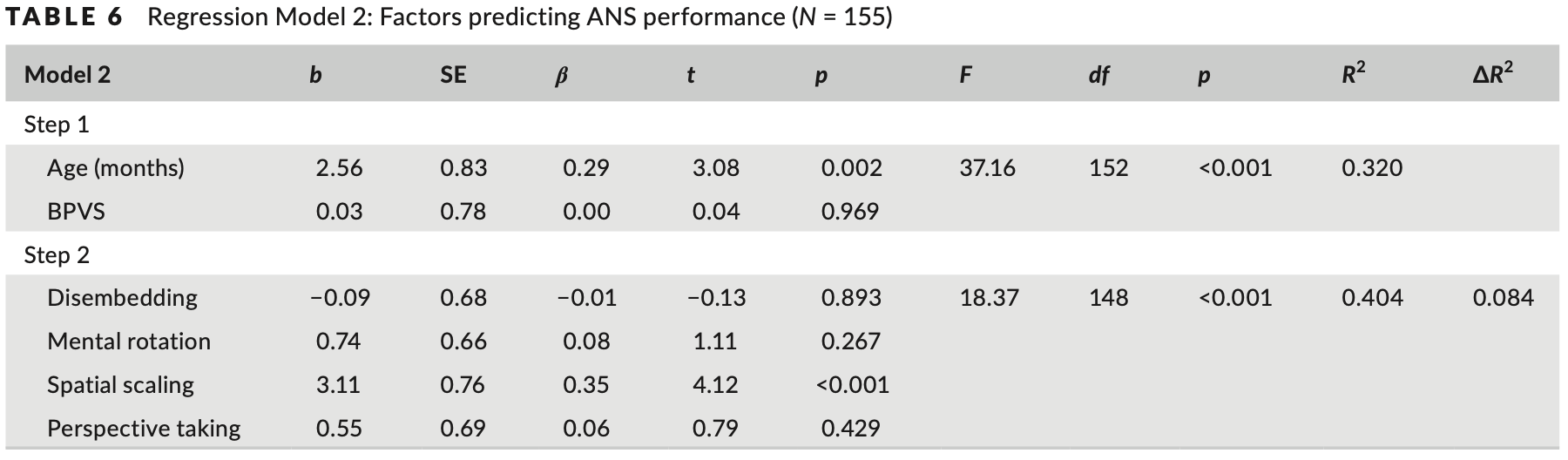

3.3.2 Model 2: Identifying predictors of ANS performance

Model 2 investigated the role of spatial skills in explaining ANS performance. The final model explained 40.4% of the variation in ANS skills. As before, the control variables were entered in step 1 and explained 32.0% of ANS variation. The four spatial measures were added in step 2, accounting for an additional 8.4% of the variation. Interaction terms between each spatial skill and age were entered in step 3. No interactions with age were retained in the final model. As shown in Table 6, spatial scaling and age were significant predictors in the final model.

3.3.2 模型 2:识别 ANS 性能的预测因子

模型 2 研究了空间技能在解释 ANS 性能中的作用。 最终模型解释了 ANS 技能差异的 40.4%。 与之前一样,控制变量在步骤 1 中输入并解释了 ANS 变异的 32.0%。 在步骤 2 中添加了四个空间测量值,占变异的额外 8.4%。 在步骤 3 中输入每个空间技能和年龄之间的交互项。最终模型中不保留与年龄的交互项。 如表 6 所示,空间尺度和年龄是最终模型中的重要预测因素。

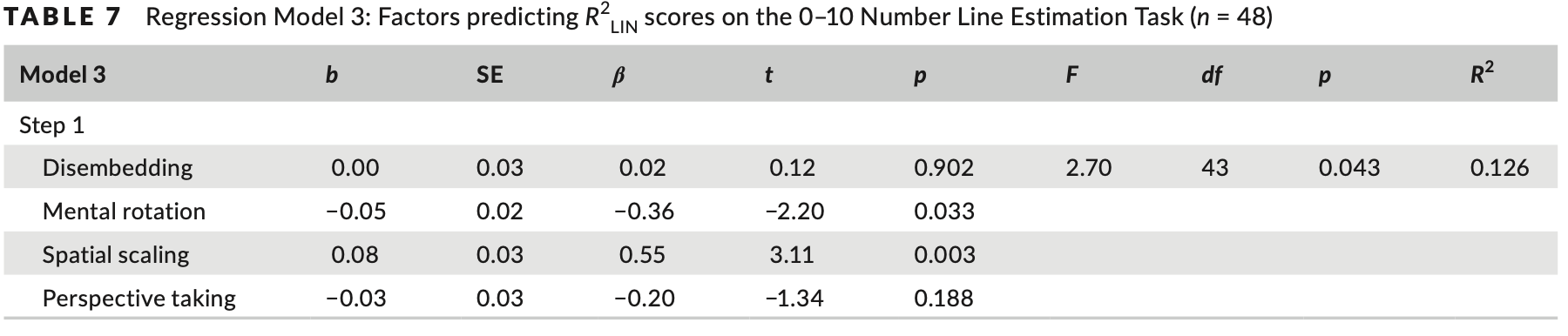

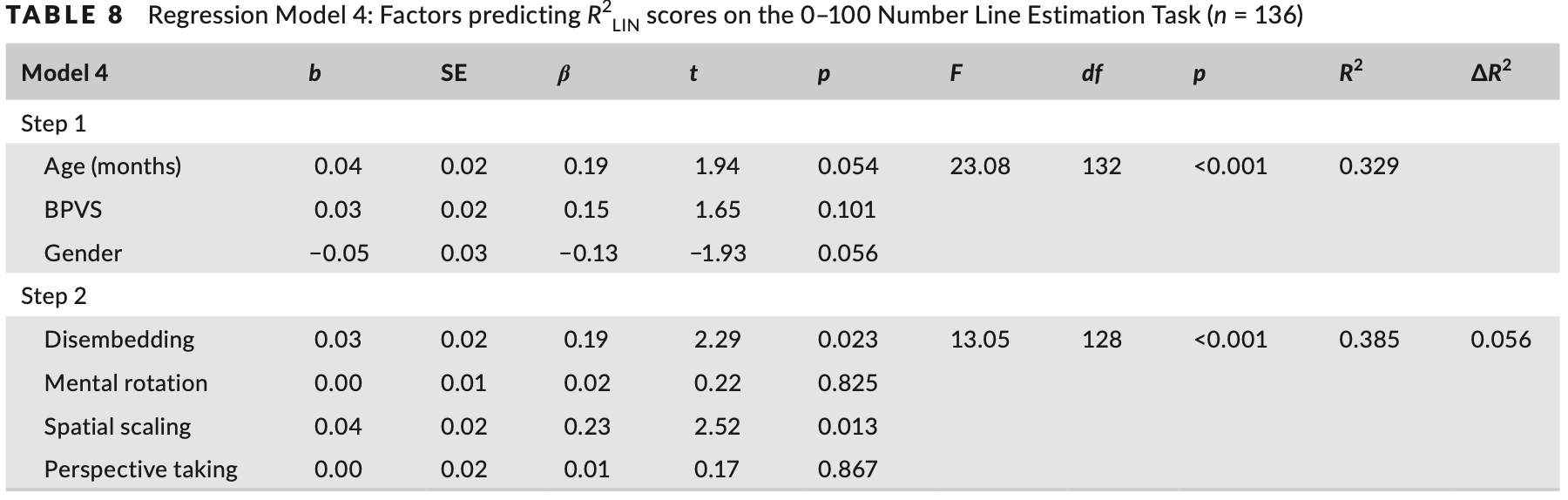

3.3.3 Model 3: Identifying predictors of 0–10 number line estimation performance

In model 3, the role of spatial skills as a predictor of R2LIN values on the 0–10 Number Line Estimation Task was explored. The control variables including gender were added in step 1 led to a negative adjusted R2 value (−3.6%). Hence, these variables were removed, and the regression was re‐run. In the revised model, the spatial tasks were added to the model in step 1, explaining 12.6% of the variation. Interaction terms between each spatial skill and age were entered in step 3; however, none were retained in the final model. The final model accounted for 12.6% of the variation. Spatial scaling and rotation were the only significant predictors (see Table 7).

3.3.3 模型 3:识别 0-10 数轴估计性能的预测变量

在模型 3 中,探讨了空间技能作为 0-10 数轴估计任务中 R2LIN 值预测因子的作用。 在步骤 1 中添加包括性别在内的控制变量导致调整后的 R2 值为负值 (-3.6%)。 因此,这些变量被删除,并重新运行回归。 在修订后的模型中,空间任务在步骤 1 中添加到模型中,解释了 12.6% 的变化。 在步骤3中输入每个空间技能和年龄之间的交互项; 然而,最终模型中没有保留任何内容。 最终模型占变异的 12.6%。 空间缩放和旋转是唯一重要的预测因素(见表 7)。

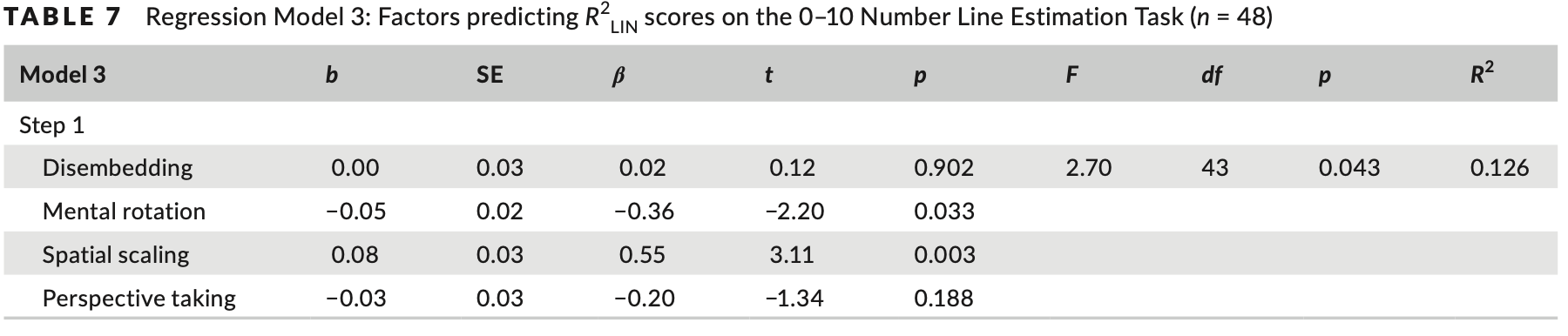

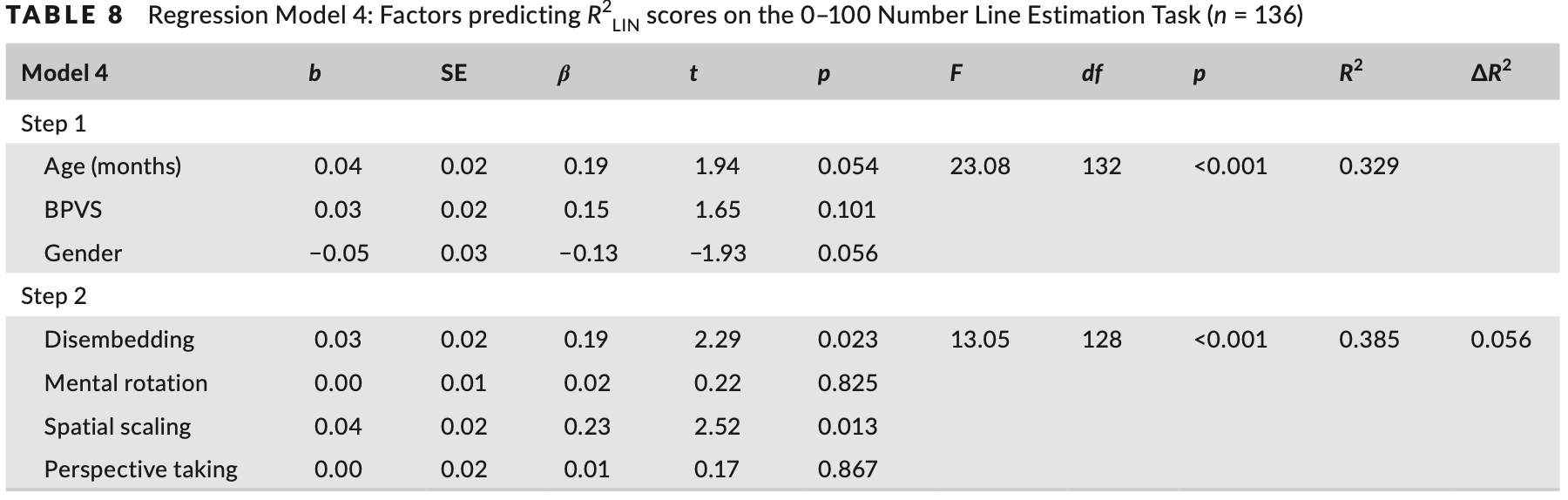

3.3.4 Model 4: Identifying predictors of 0–100 number line estimation performance

Model 4 explored the role of spatial skills in explaining R2LIN performance on the 0–100 Number Line Estimation Task. The control variables were added in step 1 and accounted for 32.9% of the variation. In step 2, the spatial skills added accounted for an additional 5.6% of the variation. None of the interaction terms added in step 3 were retained in the model. As shown in Table 8, the final model accounted for 38.5% of the variation. Disembedding and spatial scaling were significant predictors in the final model.

3.3.4 模型 4:识别 0-100 数轴估计性能的预测变量

模型 4 探讨了空间技能在解释 R2LIN 在 0-100 数轴估计任务中的性能中的作用。 控制变量是在步骤 1 中添加的,占变异的 32.9%。 在步骤 2 中,添加的空间技能额外增加了 5.6% 的变化。 步骤 3 中添加的交互项均未保留在模型中。 如表8所示,最终模型占变异的38.5%。 脱嵌和空间缩放是最终模型中的重要预测因素。

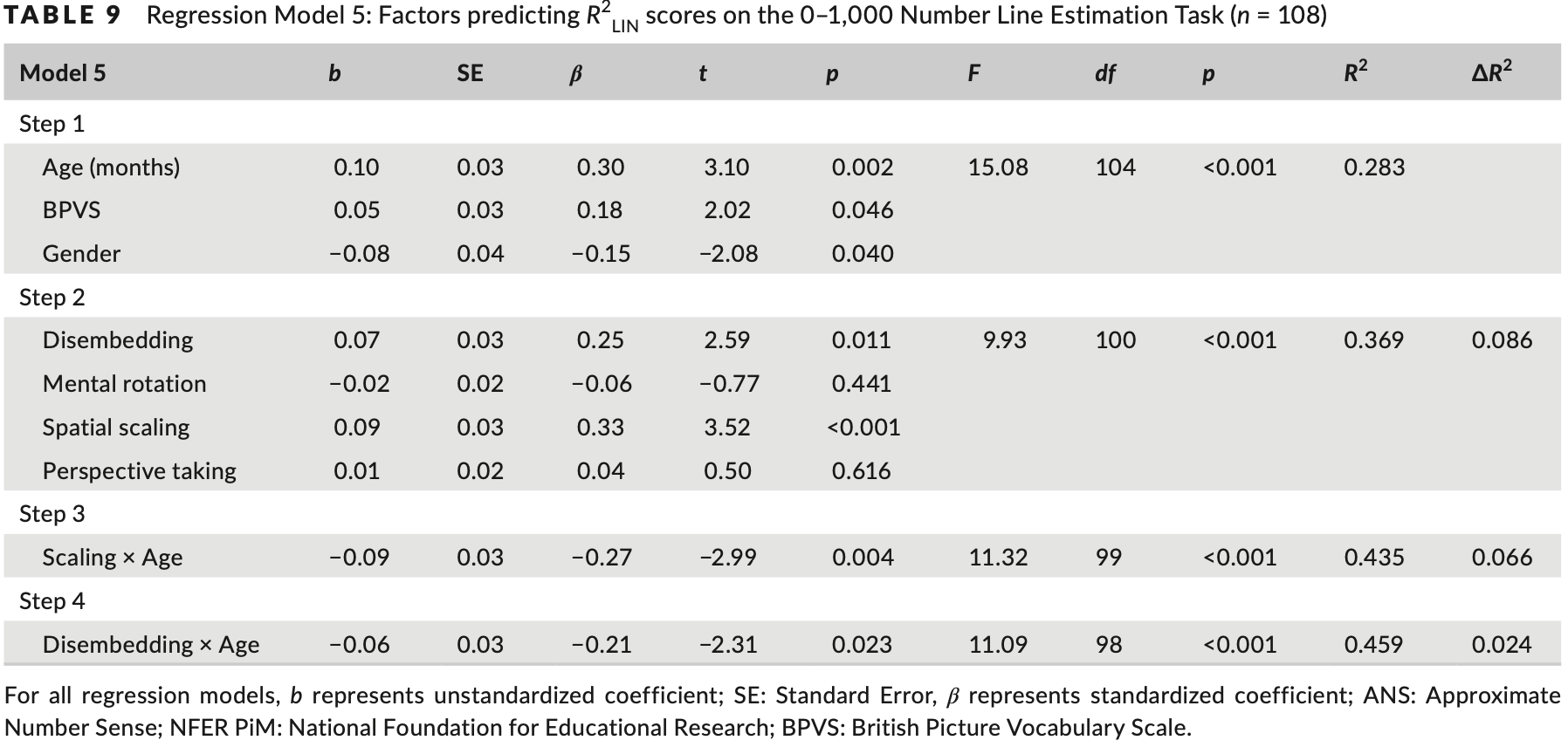

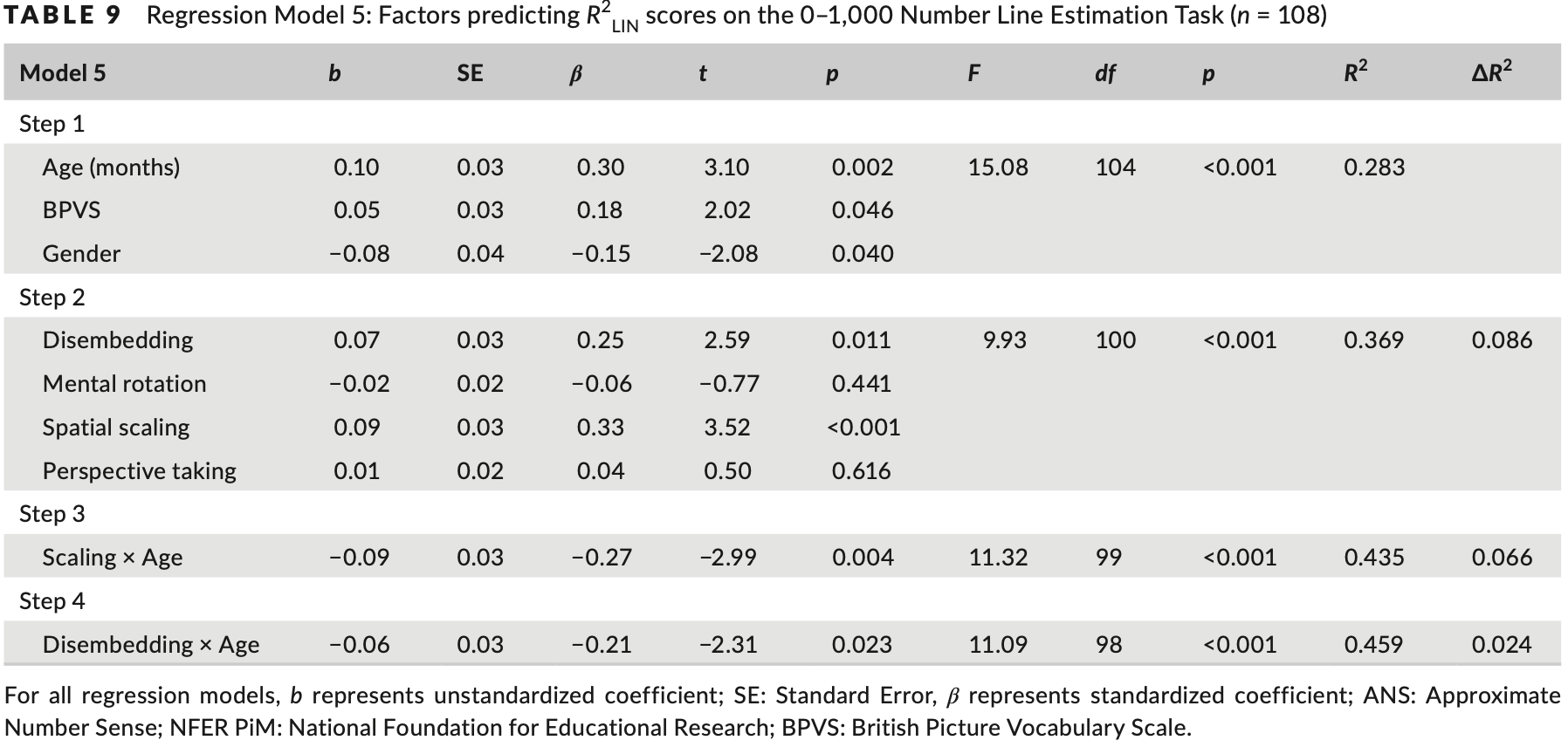

3.3.5 Model 5: Identifying predictors of 0–1,000 number line estimation performance

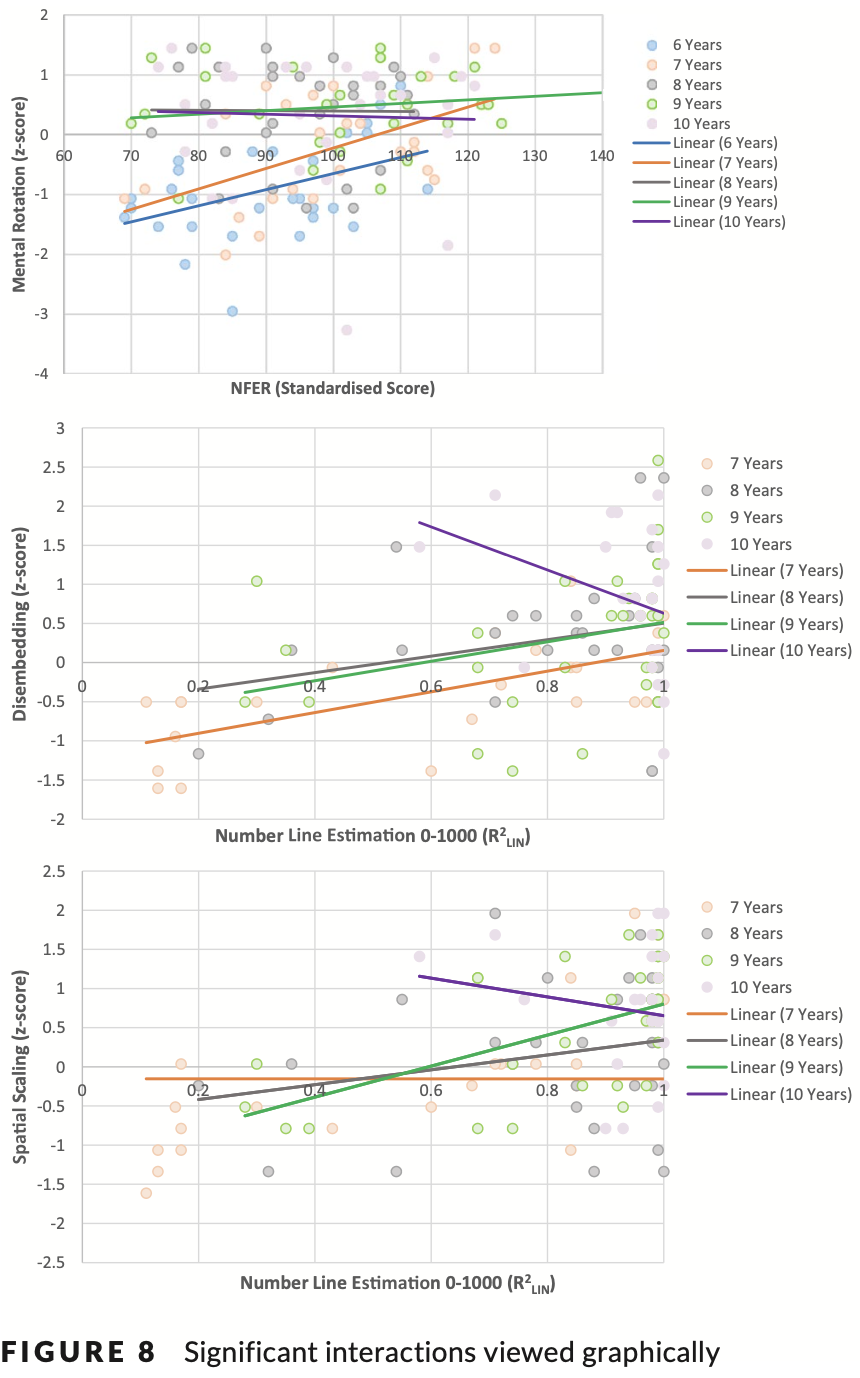

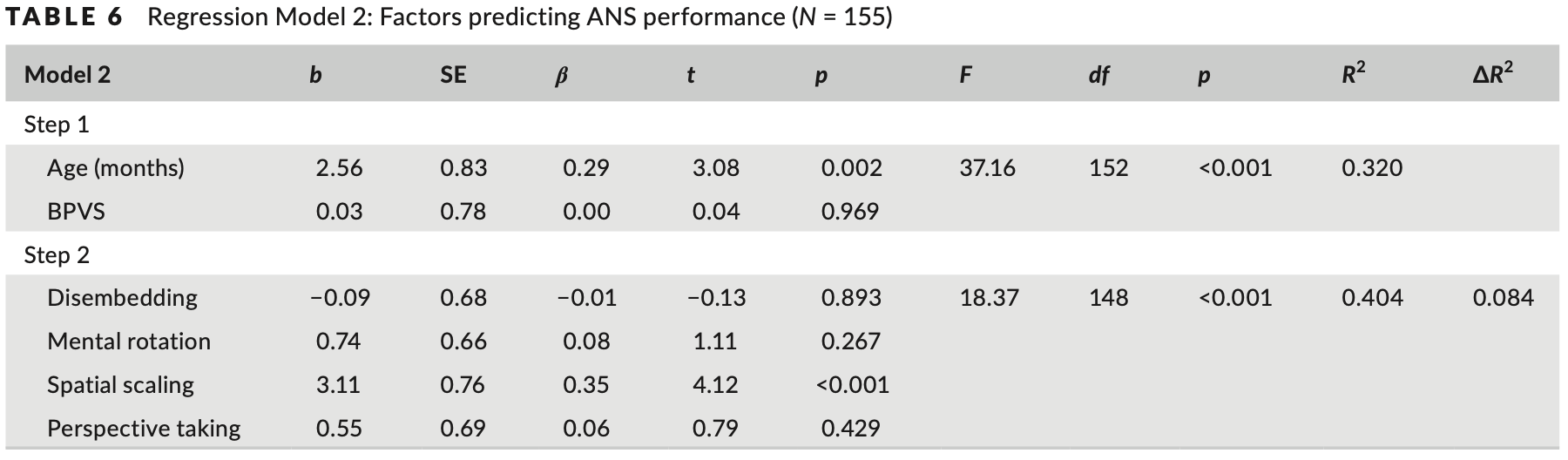

Model 5 explored the contribution of spatial skills to R2LIN scores on the 0–1,000 Number Line Estimation Task. The control variables including gender added in step 1 explained 28.3% of the variance in task performance. The spatial skills added in step 2 accounted for an additional 8.6% of the variation. In step 3, interaction terms between each spatial skill and age were added. The interactions between age and spatial scaling, and between age and disembedding were retained, explaining an additional 6.6% and 2.4% of the variation, respectively. The final model outlined in Table 9 explained 45.9% of the variation on the 0–1,000 block of the Number Line Estimation Task. Age, language ability, gender, spatial scaling, disembedding and the interaction terms (between spatial scaling and age, and disembedding and age) were significant predictors in the final model.

The interaction was explored graphically (Figure 8). For both spatial scaling and disembedding, the figure indicated a linear relationship with number line estimation performance at 7, 8 and 9 years. However, there was no linear relationship between these spatial skills and number line performance at 10 years. The figure indicated that for this task, performance at 10 years approached ceiling levels, lacked variability and was significantly negatively skewed. Thus, it was concluded that the age‐based interactions reported were likely due to a lack of variability in performance scores at 10 years and not a true age‐based effect. The interaction was not explored further.

3.3.5 模型 5:识别 0–1,000 数轴估计性能的预测变量

模型 5 探讨了空间技能对 0-1,000 数轴估计任务中的 R2LIN 分数的贡献。 步骤 1 中添加的包括性别在内的控制变量解释了任务绩效中 28.3% 的差异。 第 2 步中添加的空间技能额外增加了 8.6% 的变化。 在步骤3中,添加了每个空间技能和年龄之间的交互项。 年龄和空间尺度之间以及年龄和脱嵌之间的相互作用被保留,分别解释了额外的 6.6% 和 2.4% 的变异。 表 9 中概述的最终模型解释了数轴估计任务 0-1,000 块上 45.9% 的变异。 年龄、语言能力、性别、空间尺度、脱嵌和交互项(空间尺度和年龄之间以及脱嵌和年龄之间)是最终模型中的重要预测因素。

以图形方式探讨了交互作用(图 8)。 对于空间缩放和去嵌入,该图表明与 7 年、8 年和 9 年的数轴估计性能呈线性关系。 然而,这些空间技能和 10 年后的数轴表现之间不存在线性关系。 该图表明,对于这项任务,10 年的绩效接近上限水平,缺乏可变性,并且存在显着的负偏态。 因此,得出的结论是,报告的基于年龄的相互作用可能是由于 10 岁时的表现得分缺乏变异性,而不是真正的基于年龄的效应。 没有进一步探讨这种相互作用。

4 DISCUSSION

Spatial skills were identified as significant predictors of several mathematics outcomes, even after controlling for other known predictors of mathematics. This study was founded on a population of primary school children aged 6–10 years. For some spatial sub‐domains, their role in predicting mathematical outcomes was consistent across age groups. Spatial skills explained 12.4% of general mathematics performance with disembedding (intrinsicstatic sub‐domain) and spatial scaling (extrinsic‐static sub‐domain) identified as significant predictors. For the ANS task, although spatial skills predicted 8.4% of the variation in performance, spatial scaling (extrinsic‐static sub‐domain) was the only significant spatial predictor. In contrast, spatial skills explained 12.6%, 5.6% and 8.6% of the variation on the 0–10, 0–100 and 0–1,000 blocks of task, respectively. Spatial scaling (extrinsic‐static sub‐domain) was a significant predictor for all three blocks of the Number Line Estimation Task.

Some spatial sub‐domains had age‐dependent relations with mathematical outcomes. A role of mental rotation (intrinsic‐dynamic sub‐domain) in predicting standardised mathematics outcomes was found at 6 and 7 years only. This was reflected by the ß values reported. At 6 and 7 years, mental rotation was also a significant predictor of 0–10 number line estimation. For the 0–100 and 0–1,000 blocks of the Number Line Estimation Task, mental rotation was not a significant predictor for any age groups. These findings are consistent with Mix et al. (2016, 2017) and suggest a transition in the spatial skills that are important for mathematics, which occurs in middle childhood at approximately 7 to 8 years (Mix et al., 2016, 2017). Here, this transition is defined by a reduction in the role of mental rotation for mathematics performance. As discussed below, successful performance on mental rotation tasks requires mental visualization. Therefore, these performance patterns may reflect a reduction in the use of mental visualization strategies in the completion of certain mathematics tasks at approximately 8 years. Overall, this study reports some age‐dependent effects and indicates that for some spatial skills, their role in predicting mathematics changes through development.

These results support multi‐dimensional models of spatial thinking (Buckley, Seery, & Canty, 2018). The four spatial predictors included in this study (measuring each of Uttal et al.'s (2013) and Newcombe and Shipley's (2015) four theoretically motivated spatial sub‐domains) were found to have varying roles in explaining mathematics outcomes. Previous studies of primary school children have typically explored associations between intrinsic‐dynamic spatial tasks and mathematics. The results of this study highlight the importance of other spatial sub‐domains in explaining mathematics outcomes, particularly spatial scaling (extrinsic‐static sub‐domain). Thus, failures to find significant spatial‐mathematical associations in some previous studies may reflect the limited spatial sub‐domains assessed or the age of the participants tested (Carr, Steiner, Kyser, & Biddlecomb, 2008).

4 讨论

即使在控制了其他已知的数学预测因素之后,空间技能也被认为是多种数学结果的重要预测因素。 这项研究以 6 至 10 岁的小学生为对象。 对于某些空间子域,它们在预测数学结果方面的作用在不同年龄组中是一致的。 空间技能解释了 12.4% 的一般数学表现,其中去嵌入(内在静态子域)和空间尺度(外在静态子域)被认为是重要的预测因素。 对于 ANS 任务,虽然空间技能预测了 8.4% 的性能变化,但空间尺度(外在静态子域)是唯一重要的空间预测因子。 相比之下,空间技能分别解释了 0-10、0-100 和 0-1,000 个任务块的 12.6%、5.6% 和 8.6% 的变化。 空间尺度(外在静态子域)是数轴估计任务的所有三个块的重要预测因子。

一些空间子域与数学结果存在年龄依赖性关系。 仅在 6 岁和 7 岁时才发现心理旋转(内在动态子域)在预测标准化数学结果中的作用。 报告的 ß 值反映了这一点。 在 6 岁和 7 岁时,心理旋转也是 0-10 数轴估计的重要预测因素。 对于数轴估计任务的 0-100 和 0-1,000 块,心理旋转并不是任何年龄组的显着预测因素。 这些发现与 Mix 等人的观点一致。 (2016, 2017) 并提出对数学很重要的空间技能的转变,这种转变发生在童年中期大约 7 至 8 岁的时候 (Mix et al., 2016, 2017)。 在这里,这种转变是通过心理旋转对数学表现的作用的减少来定义的。 如下所述,成功完成心理旋转任务需要心理可视化。 因此,这些表现模式可能反映出在大约 8 岁时完成某些数学任务时心理可视化策略的使用减少。 总的来说,这项研究报告了一些与年龄相关的影响,并表明对于某些空间技能来说,它们在预测数学发展过程中的变化中发挥着作用。

这些结果支持空间思维的多维模型(Buckley、Seery 和 Canty,2018)。 研究发现,本研究中包含的四个空间预测因子(分别测量 Uttal 等人(2013 年)以及 Newcombe 和 Shipley(2015 年)的四个理论上驱动的空间子域)在解释数学结果方面具有不同的作用。 先前对小学生的研究通常探索内在动态空间任务与数学之间的关联。 这项研究的结果强调了其他空间子域在解释数学结果方面的重要性,特别是空间尺度(外在静态子域)。 因此,在之前的一些研究中未能发现显着的空间数学关联可能反映了评估的有限空间子域或测试参与者的年龄(Carr、Steiner、Kyser 和 Biddlecomb,2008)。

4.1 Mechanisms underpinning spatial– mathematics associations

Spatial scaling was a significant predictor of all mathematics measures in this study. In line with (Möhring et al., 2015), shared proportional reasoning requirements are highlighted here, as a likely underlying mechanism explaining these findings. For the Number Line Estimation Task, there is a clear role for proportional reasoning. For example, 28 can be positioned on a 0–100 number line with relatively high accuracy by dividing the line into four portions. For standardized mathematics performance, there are a range of mathematics topics that may require proportional reasoning such as reasoning about fractions or completing area and distance questions. For the ANS Task, proportional reasoning can be used to compare the ratios of the dot arrays presented. The relations between spatial scaling and ANS performance suggest that associations between scaling and mathematics are not caused by a symbolic number mechanism such as the Mental Number Line, as symbolic number representations are not required for dot comparison in the ANS Task. Taken together, these findings support the concept that proportional reasoning may be the underlying shared cognitive mechanism between spatial scaling and mathematics skills.

Disembedding was a significant predictor of both number line estimation and standardized mathematics performance. These associations may be attributable to shared form perception demands of these tasks. Form perception is the ability to distinguish shapes and symbols (Mix et al., 2016). As outlined in the introduction, for standardized mathematics, form perception is theoretically useful for distinguishing symbols and digits such as + and × symbols, interpreting charts, and completing multistep calculations (Landy & Goldstone, 2007, 2010; Mix et al., 2016). For the Number Line Estimation Task, form perception is required for the identification of numeric symbols and use of symbols and for interpreting and using the visual diagrams presented.

Finally, mental rotation was a significant predictor of mathematics outcomes for younger participants only. For both standardized mathematics and the 0–10 block of the Number Line Estimation Task, mental rotation was a significant predictor at 6 and 7 years. It is proposed that mental rotation requires active processing including mental visualization (Lourenco et al., 2018; Mix et al., 2016). The findings reported here suggest that younger children may use mental models to visualize problems, including mathematics problems. Mental visualizations may be used to represent and organize complex word problems or mathematical relationships (Huttenlocher et al., 1994; Laski et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2013). The results reported in this study also suggest that the use of mental visualization strategies in mathematics is less common in older age groups. That is not to say that mental models do not play a role in the completion of more abstract mathematical tasks encountered in later schooling, for example, visualizing graphs in 3‐D, plotting vectors, graphing functions from equations. However, for the specific mathematics tasks included in this study, an age effect of mental model use was found.

As outlined in the introduction, the Perspective Taking Task was also hypothesized to recruit mental visualizations. However, this task was not a significant predictor of any of the mathematics outcomes. These findings highlight an important distinction between different types of mental visualizations based on the frame of reference being transformed. Hegarty and Waller (2004) found that object transformation ability and viewer/perspective transformation ability are two distinct spatial factors. Here, we suggest that these two mental transformation abilities are differentially associated with mathematics in children. Egocentric object‐based transformations (required for mental rotation and other intrinsicdynamic tasks) are important for mathematics; however allocentric viewer transformations (as required for perspective taking and other extrinsic‐dynamic tasks) are not (at least for the age‐range measured). This is an important distinction, particularly for the design of training studies targeting mental visualization skills. These findings are consistent with Mix et al. (2016, 2017) who did not find that perspective taking loaded significantly onto mathematics at 6, 9 or 11 years. However, there was a significant cross‐factor loading of mental rotation onto mathematics at 6 years (not age 9 or 11 years). Taken together, the findings in this study provide evidence for the proposal that there are different explanations underpinning spatial‐mathematical associations, depending on the mathematical and spatial sub‐domains assessed (Fias & Bonato, 2018).

4.1 支持空间数学关联的机制

空间尺度是本研究中所有数学测量的重要预测因素。 根据(Möhring 等人,2015),这里强调了共享的比例推理要求,作为解释这些发现的可能的潜在机制。 对于数轴估计任务,比例推理有明显的作用。 例如,通过将 0-100 数轴分为四部分,可以以相对较高的精度将 28 定位在该数轴上。 对于标准化数学表现,有一系列数学主题可能需要比例推理,例如分数推理或完成面积和距离问题。 对于 ANS 任务,可以使用比例推理来比较所呈现的点阵列的比率。 空间缩放和 ANS 性能之间的关系表明,缩放和数学之间的关联不是由心智数轴等符号数字机制引起的,因为 ANS 任务中的点比较不需要符号数字表示。 总而言之,这些发现支持了这样的概念:比例推理可能是空间尺度和数学技能之间潜在的共享认知机制。

去嵌入是数轴估计和标准化数学表现的重要预测因素。 这些关联可能归因于这些任务的共享形式感知需求。 形式感知是区分形状和符号的能力(Mix et al., 2016)。 正如引言中所述,对于标准化数学,形式感知理论上对于区分符号和数字(例如 + 和 × 符号)、解释图表以及完成多步计算非常有用(Landy & Goldstone,2007、2010;Mix 等人,2016) 。 对于数轴估计任务,需要形式感知来识别数字符号和符号的使用以及解释和使用所呈现的视觉图表。

最后,心理旋转只是年轻参与者数学成绩的重要预测因素。 对于标准化数学和数轴估计任务的 0-10 块,心理旋转是 6 岁和 7 岁时的重要预测因素。 有人提出,心理旋转需要主动处理,包括心理可视化(Lourenco et al., 2018;Mix et al., 2016)。 这里报告的研究结果表明,年幼的孩子可能会使用心理模型来想象问题,包括数学问题。 心理可视化可用于表示和组织复杂的文字问题或数学关系(Huttenlocher 等,1994;Laski 等,2013;Thompson 等,2013)。 这项研究报告的结果还表明,在年龄较大的群体中,在数学中使用心理可视化策略不太常见。 这并不是说心理模型在完成以后学校教育中遇到的更抽象的数学任务中不起作用,例如,可视化 3D 图形、绘制向量、绘制方程中的函数。 然而,对于本研究中包含的特定数学任务,发现了心智模型使用的年龄效应。

正如引言中所述,换位思考任务也被假设为招募心理可视化。 然而,这项任务并不是任何数学结果的重要预测因素。 这些发现强调了基于正在转换的参考框架的不同类型的心理可视化之间的重要区别。 Hegarty 和 Waller (2004) 发现物体变换能力和观察者/视角变换能力是两个不同的空间因素。 在这里,我们认为这两种心理转变能力与儿童的数学有不同的联系。 以自我为中心的基于对象的转换(心理旋转和其他内在动力任务所需)对于数学很重要; 然而,异中心观看者转换(根据视角拍摄和其他外在动态任务的需要)却不是(至少对于测量的年龄范围而言)。 这是一个重要的区别,特别是对于针对心理可视化技能的培训研究的设计。 这些发现与 Mix 等人的观点一致。 (2016,2017)他们没有发现观点采择对 6、9 或 11 岁时的数学有显着影响。 然而,在 6 岁(不是 9 岁或 11 岁)时,数学上存在显着的心理旋转负荷。 总而言之,本研究的结果为以下提议提供了证据:根据评估的数学和空间子领域,支持空间数学关联有不同的解释(Fias & Bonato,2018)。

4.2 The role of control variables

This study highlights associations between vocabulary and mathematics performance. Accounting for spatial ability and the other control variables, vocabulary remained a significant predictor of standardized mathematics performance, and the most difficult 0–1,000 Number Line Estimation Task only. These findings are consistent with previous evidence that language skills are a significant longitudinal predictor of general mathematics achievement, controlling for spatial ability, in the early primary and pre‐school school years (Gilligan et al., 2017; LeFevre et al., 2010). The results are also consistent with findings that language is a significant predictor of science achievement in the primary school years, controlling for spatial thinking (Hodgkiss et al., 2018). Taken together, the evidence suggests that language and spatial skills have distinct relations to mathematics (and science).

No significant performance differences were found between males and females on any of the spatial tasks included in the study. Historically, other studies have reported a male advantage in spatial task performance in childhood (e.g. Carr et al., 2008; Casey et al., 2008). However, the results of this study add to the growing body of literature arguing that the spatial performance of girls and boys is equivalent (e.g. Gilligan et al., 2017; Halpern et al., 2007; LeFevre et al., 2010). In the domain of mathematical cognition, a significant male advantage was found for 0–100 (d = 0.38) and 0–1,000 (d = 0.52) number line estimation performance only. This is consistent with previous mixed findings in this domain, such that some studies argue for (Gilligan et al., 2017; Halpern et al., 2007; Penner & Paret, 2008) and others argue against (Lindberg, Hyde, Petersen, & Linn, 2010) gender differences in mathematics performance. The findings reported in this study suggest that gender differences in mathematics performance are task‐specific. Differences in the mathematics outcomes used across previous studies may account for the variable results reported.

4.2 控制变量的作用

这项研究强调了词汇和数学成绩之间的关联。 考虑到空间能力和其他控制变量,词汇量仍然是标准化数学成绩的重要预测因素,而且仅适用于最困难的 0-1,000 数轴估计任务。 这些发现与之前的证据一致,即在小学早期和学前教育阶段,控制空间能力,语言技能是普通数学成绩的重要纵向预测因素(Gilligan 等,2017;LeFevre 等,2010) 。 研究结果也与以下发现一致:语言是小学科学成绩的重要预测因素,控制着空间思维(Hodgkiss 等人,2018)。 综上所述,证据表明语言和空间技能与数学(和科学)有着独特的关系。

在研究中的任何空间任务上,男性和女性之间没有发现显着的表现差异。 历史上,其他研究也报道过男性在童年空间任务表现方面具有优势(例如 Carr 等人,2008 年;Casey 等人,2008 年)。 然而,这项研究的结果增加了越来越多的文献认为女孩和男孩的空间表现是相当的(例如 Gilligan 等人,2017 年;Halpern 等人,2007 年;LeFevre 等人,2010 年)。 在数学认知领域,男性仅在 0-100 (d = 0.38) 和 0-1,000 (d = 0.52) 数轴估计表现上具有显着优势。 这与该领域之前的混合发现一致,因此一些研究支持(Gilligan et al., 2017; Halpern et al., 2007; Penner & Paret, 2008),而其他研究则反对(Lindberg, Hyde, Petersen, & Linn,2010)数学成绩的性别差异。 本研究报告的结果表明,数学成绩的性别差异是特定于任务的。 先前研究中使用的数学结果的差异可能是报告结果可变的原因。

4.3 Future directions and limitations

In summary, spatial skills were significant predictors of performance across all mathematics measures, explaining approximately 5%–14% of the individual variation in performance. These results suggest that training spatial thinking would confer benefits for both spatial and mathematics outcomes. There are mixed findings on the transfer of training gains (to untrained domains) in other cognitive domains such as working memory (for a review see (Melby‐Lervåg, Redick, & Hulme, 2016)). However, we suggest that far transfer of training gains is constrained by an understanding of the underlying cognitive mechanisms of training targets. Thus, the proposed task and age‐dependent explanations for spatial–mathematics associations, strengthen the likelihood of far transfer of gains. For example, the findings of this study suggest that spatial scaling training would lead to improvements in ANS performance given the proposed proportional reasoning requirements of both tasks. However, there is no evidence to suggest that mental rotation training would render ANS performance gains. As such, this study highlights the importance of choosing theoretically motivated, taskand age‐sensitive targets for spatial training. This study does not offer insight into the causal relationship between spatial and mathematical thinking. Although mathematics skills may play a causal role in spatial performance, given the educational importance of mathematics, this study proposes that future training studies explore a possible causal role of spatial skills for mathematical thinking. To understand the causal relationship between specific spatial and mathematical skills, training on specific spatial tasks is required. There is evidence that spatial training, in which spatial thinking is embedded into mathematical instruction, leads to gains in spatial and mathematics outcomes (geometry performance) in children aged 6 (Hawes et al., 2017) and 11 years (Lowrie et al., 2017). However, while these findings have useful classroom applications, they cannot offer insights into the causal relationship between spatial and mathematical skills, as the mathematical and spatial aspects of training cannot be disentangled.

This study highlights spatial scaling as a particularly useful target for spatial skill training (0.23 < β < 0.55, across mathematics outcomes). We propose two reasons for these findings. First, there is a proposed underlying mechanism (proportional reasoning) linking each of the mathematics tasks in this study to spatial scaling. There is no theoretical reason to predict that spatial scaling would be associated with all mathematics tasks, particularly those with no proportional reasoning requirement, for example, multi‐digit calculation. Second, in spatial scaling tasks, participants are required to compare two differently scaled spaces (i.e. it is an extrinsic‐static task). However, in the context of an individual object, scaling can also be viewed as an object transformation, that is, expanding or contracting an object (Newcombe & Shipley, 2015). Object transformations like this are required in intrinsic‐dynamic tasks. In this way, spatial scaling tasks may elicit both proportional reasoning and mental transformation, two processes that are required for different mathematics tasks. The results also highlight mental rotation and disembedding as potential spatial training targets, for some but not all aspects of mathematics, at certain ages. In support of this, gains in calculation performance have been reported following mental rotation training (intrinsic‐dynamic spatial skills) in young children (Cheng & Mix, 2014). However, in another study, mental rotation training was unsuccessful in eliciting mathematical gains in children (Hawes et al., 2015). While the findings reported here suggest that, theoretically, mental rotation training should render gains in some mathematics tasks (such as missing term problems, balancing equations and word problems), future research is required to explore the features of training that might lead to such gains.

This study is the first to explicitly compare the role of Uttal et al.'s (2013) four sub‐domains of spatial thinking in explaining mathematics outcomes. Despite including all of Uttal et al.'s (2013) sub‐domains, this study focuses on small‐scale spatial thinking only. This involves table‐top tasks, where there is no need for whole‐body movement or for changing location (Broadbent, 2014). Future work might extend these findings to include largescale spatial processes which require movement and observations from a number of vantage points, for example, using real world or virtual navigation tasks (Kuipers, 1978, 1982). Similarly, while this study is the first to explore associations between spatial and mathematics skills in children aged 6 to 10 years using a crosssectional approach, the findings could be strengthened by longitudinal research following a single cohort of participants through development from 6 to 10 years.